Part of doing one’s job as a lawman is understanding when to talk and when to listen. “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” is a film about hard people who have an even harder time listening to the people in their lives. A study in the crushing effect of tragedy and the importance of empathy, it might be the year’s best film.

Part of doing one’s job as a lawman is understanding when to talk and when to listen. “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” is a film about hard people who have an even harder time listening to the people in their lives. A study in the crushing effect of tragedy and the importance of empathy, it might be the year’s best film.

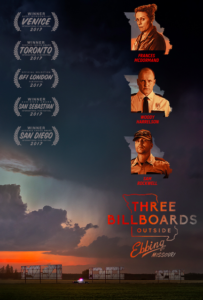

In “Three Billboards,” Chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), who is facing his own mortality, is confronted with his most frustrating case—an unsolved murder/rape. The murdered girl’s grieving mother, Mildred (Frances McDormand), decides to call the Chief out by purchasing three billboards in the town questioning very publicly the Chief’s commitment to the case.

Naturally, this causes quite a stir. And because the Chief is dying of cancer, people in the town are against Mildred’s crusade. The Chief’s favorite deputy, the miserable Dixon (Sam Rockwell), wants the billboards taken down even if that means using violence.

The film sets up many of the familiar elements we’ve seen in classic Westerns. But trust me, what feels familiar, isn’t. As the narrative unfolds, the story moves in unusual ways. Mildred, the Chief, Dixon, the town are all going through a transition. And circumstances just might force them all to listen to one another.

British filmmaker McDonagh gets the speech pattern of the divided midwestern/southern state of Missouri down by crafting dialogue that feels undeniably authentic. And, of course, it helps that McDonagh’s words are performed by some of the best and most interesting faces working today.

Led by Oscar winner McDormand, the cast is as rich and layered as the complex plotting. These are well-worn actors who bite down hard on their grizzled characters. Harrelson, who is just about everywhere these days, gives one of his best performances literally shocking us in one scene, that I dare not spoil, where his reaction combined with that of McDormand will cause your heart to melt. And McDonagh understands exactly when to change the tone for maximum impact.

The faces move mountains here. Caleb Landry Jones, who we’ve seen a lot this year (even in a key scene in awards-darling “The Florida Project”), plays the ad man who agrees to put Mildred’s messages on his billboards. He’s a distinctive looking guy, but when you put him in a scene with McDormand and Rockwell, it is literally like a perverse Norman Rockwell. And instead of a sweet depiction of Americana, there is something dangerous and mean festering underneath.

Things unspoken linger between Mildred and her ex-husband, Charlie (a menacing John Hawkes). It is sinister and disturbing. Having moved on, Charlie’s new woman is a naive child, who acts brainless but might just be hanging on because events in her young life require the stability offered by an older man. When Mildred and Charlie are in a room together, the tension is almost unbearable. And this subplot is not even the focus of the film. McDonagh constantly keeps us guessing making the film increasingly interesting and rewarding.

In the upcoming “Phantom Thread,” Daniel Day-Lewis plays a dress-maker who alienates himself for the sake of his work. There are lots of shots of him lost in thought, just, thinking. His level of contemplation is telling and instructive.

I mention this, because in “Three Billboards,” the characters only make time for reflection after some terrible event has taken place. They realize, perhaps too late, that they can’t take back the awful things they do to one another. Regret hangs about pushing them all down, and finding the will to move on is what makes this narrative sing. It’s never too late to learn something new about yourself and the people in your life.