“Curvature” is a handsomely made, well acted, intricately constructed sincere science fiction indie. By contrast, “Astro” is none of those things.

Working on a modest budget, filmmakers who understand the limitations can achieve unique and wonderful results. Over the years, I’ve repeatedly pointed to Shane Carruth’s “Primer” as superior example of inventive and satisfying zero budget science fiction. But the SF genre has consistently been a place for small budget cinema. For a print newspaper, I recently reviewed SyFy’s “Krypton,” a series with significant resources that still managed to look cheap with it’s dated dark look. Of course, it didn’t help that the DC comics inspired story failed to rise to its high concept promise.

Working on a modest budget, filmmakers who understand the limitations can achieve unique and wonderful results. Over the years, I’ve repeatedly pointed to Shane Carruth’s “Primer” as superior example of inventive and satisfying zero budget science fiction. But the SF genre has consistently been a place for small budget cinema. For a print newspaper, I recently reviewed SyFy’s “Krypton,” a series with significant resources that still managed to look cheap with it’s dated dark look. Of course, it didn’t help that the DC comics inspired story failed to rise to its high concept promise.

And back in May, I reviewed “The Endless,” a film that clearly owes a big debt to the indie SF titles over the last 20 plus years. Co-directors Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead, who also starred in that film, managed to deliver a trippy flick without breaking the bank. Being smart is critical regardless whether you have named actors or grandiose special effects.

When a passionate filmmaker, sometimes just starting out, decides to make a science fiction feature film, ambition can be that filmmaker’s downfall. Case in point: “Astro,” from writer/director Asif Akbar, who has a number of ideas, but sorely lacks the necessary tools to pull them off. He’s populated his picture with actors known for action and names certainly capable crafting memorable characterizations. But given Akbar’s in attentiveness to the cinematic form (more homework is needed), the script features dialogue so pedantic that it is as though each action a character takes is tediously narrated.

By contrast, filmmaker Diego Hallivis with his modestly budgeted “Curvature” has delivered a picture commiserate with his budgetary restraints. And despite what my snarky critic brethren have said about the film, Hallivis has achieved a measure of success that exceeded my expectations. Like the similarly budgeted “Anti-Matter” that I reviewed last year, “Curvature” is a credible feature that takes it’s science seriously, even though the fiction part is what proves to be most fun.

In “Curvature,” we meet Helen (Lyndsy Forseca) following the suicide of her husband Wells (Noah Bean). Like her, Wells is a well-educated scientist, who, on the eve of his death, made a breakthrough. One morning she awakes to discover that days have passed while she slept. A mysterious phone call warns her that she’s being pursued by a dangerous man. Naturally, she has to run in order to survive and find out the truth.

In “Curvature,” we meet Helen (Lyndsy Forseca) following the suicide of her husband Wells (Noah Bean). Like her, Wells is a well-educated scientist, who, on the eve of his death, made a breakthrough. One morning she awakes to discover that days have passed while she slept. A mysterious phone call warns her that she’s being pursued by a dangerous man. Naturally, she has to run in order to survive and find out the truth.

“Astro,” on the other hand, also features a paranoid science fiction chase narrative, but it lacks the sophistication required to sell anything that appears on screen. The story is like an entire season of “The X Files” as retold by a twelve-year-old. There’s all manner of action and ideas thrown into the mix, but it’s shot and staged so poorly that it isn’t even worthy of consideration for a short mention in an episode of “How Did This Get Made.”

“Astro,” on the other hand, also features a paranoid science fiction chase narrative, but it lacks the sophistication required to sell anything that appears on screen. The story is like an entire season of “The X Files” as retold by a twelve-year-old. There’s all manner of action and ideas thrown into the mix, but it’s shot and staged so poorly that it isn’t even worthy of consideration for a short mention in an episode of “How Did This Get Made.”

The differences between these two similarly budgeted productions is instructive. Fans of SF are some of the most forgiving, provided that you don’t insult them. Interesting ideas often trump effects, and budgetary limitations can be overcome with wit and a small amount of thinking. On my day job as an entertainment attorney, when I read business plans for such films, the pitches often explain that the SF genre has produced consistent returns for investors, perhaps, more than any other genre. It’s all a numbers game in which the right combination of factors including the Sci-fi (“SF” to purists) label could be a solid investment risk.

But while “Curvature” director Hallivis clearly understood the genre’s beats, he and his professional team well knew that their film had to also be smart. Therefore, he has a scene in which his heroine Helen solves an actual mathematical equation crucial to helping to unlock the mystery.

In “Astro,” on the other hand, writer/director Akbar borrows his plot beats from the Ed Wood school. And sadly, there’s no joy in watching the movie even as an example of bad cinema. Even though he has a cast of actors with name recognition and natural charisma, he chooses to have them sleepwalk though repetitive scenes that seem more concerned with what’s on the dinner menu (literally we get discussions about barbecuing and cooking supper) than thwarting a madman’s plans for using alien technology to take a trip to Mars. It’s laughably bad.

Okay, that was tipping over to snarky critic territory. And to be fair, my intent here isn’t to pick on a extremely low budgeted film like “Astro” made by a guy whose ambition was his downfall. There are a few scenes in space involving an astronaut looking down at earth that are visually striking. However, given the computer generated space ship shots that follow, that look very poor, it appears that the astronaut shots are not the work of the team making the m ovie, rather, well selected stock footage. There’s nothing wrong with use of stock footage, but to pair the professional with the amateur is so uneven that it undercuts the entire movie.

ovie, rather, well selected stock footage. There’s nothing wrong with use of stock footage, but to pair the professional with the amateur is so uneven that it undercuts the entire movie.

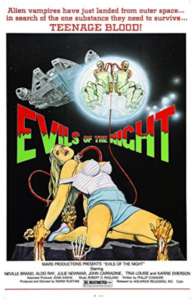

And “Astro” has a great b-movie cast led by martial artist Gary Daniels. We get the likes of Michael Pare and “My Big Fat Greek Wedding” alum Louis Mandylor. And one of the film’s villains is played by Marshal Hilton, an actor with great scene chewing potential. What could have been a nice slab of cheddar is weighed down by an almost comically serious tone. Nothing in the film is funny not even unintentionally. Sadly, “Astro” has more in common with Mohammed Rustam’s infamous 1985 film “Evils of the Night” than with anything approximating good science fiction. And “Evils” is a much better made film, which is absolutely ridiculous.

Compare “Curvature” in which the characters genuinely engage one another moving key plot elements along swiftly. Dialogue is expositive when needed but carefully considered and crafted. Gone are lines that seem completely improvised, like in “Astro,” where characters painfully state the obvious over and over.

Not a week goes by without my email inbox filling up with distributors (October Coast and Uncork’d, I’m talking about you) teasing their latest horror and SF offerings. I need to watch more of them, but there is such little time. But in watching movies made for the love of the process, this long-time film critic can get excited about covering film again.

Not a week goes by without my email inbox filling up with distributors (October Coast and Uncork’d, I’m talking about you) teasing their latest horror and SF offerings. I need to watch more of them, but there is such little time. But in watching movies made for the love of the process, this long-time film critic can get excited about covering film again.

My job as a workmanlike film critic isn’t to destroy a filmmaker’s dreams with snarky and unpleasant phrases meant to pad my own ego. My job is to inform readers and try to spare them time wasted on unworthy projects, no matter what the budget is. My job is also to champion films that some viewers might otherwise overlook. And while something unique rarely crosses my desk, I have to reference “Ratatouille” and remind readers of the words of Anton Ego (voiced by the iconic Peter O’Toole): “But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new.”

Take a look at the reviews section, do you share my taste? If so, maybe my opinion, developed over the last 20 years of writing about cinema, is consistent with your own. Maybe I can help you decide whether to spend your time and money on a particular film.

It’s so easy to pop on Netflix and watch the Marvel canon for the ninetieth time. I’ve been there, done that, but choosing the safe film over the risk can be daunting. Therefore, every month, I’ll check out one or more of these smaller films and try to help readers navigate the ocean of programming that mostly qualify as “content” rather than cinema. And even bad cinema can avoid the dreaded content label.

“Astro” is content. “Curvature” is cinema and a world worth escaping into.