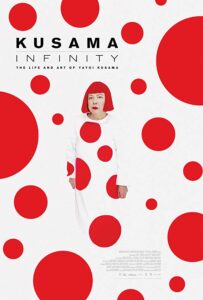

Exploring the thin line between madness and genius, director Heather Lenz vividly chronicles the life of artist Yayoi Kusama.

Dots, thousands and thousands of them. Nets, each loop painted with individual precision. Soft sculpture, with a distinctly sexual origin. And the creator is a small in stature Japanese artist, a woman driven by a lifetime of creative mania.

Dots, thousands and thousands of them. Nets, each loop painted with individual precision. Soft sculpture, with a distinctly sexual origin. And the creator is a small in stature Japanese artist, a woman driven by a lifetime of creative mania.

The expressive nature of art manifests itself is an unmeasurable number of ways. And when young Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama reached out to Georgia O’Keeffe, she was inspired by the famous painter’s response. This ultimately led Kusama to escape the confines of her traditional and comfortable Japanese family’s life and venture to the dangerous city of New York. But once she arrives in the Big Apple, Kusama realizes that making it as an artist is tough enough, but to be foreign and a woman is doubly hard.

Through strong conviction and a bit of insanity, Kusama carves out a controversial, if also, initially unsuccessful (commercially) early career. But those early experiences shaped her in important aspects, leading to a fantastic, late in life rebirth. Today, according to the film, she is one of the top (if not the top) selling female artists in the world.

Lenz smartly puts her camera primarily on Kusama’s art, while also giving us her origin story as a backdrop. What is marvelous is the film’s unbridled access to the work, and Lenz’ capably juxtapositions Kusama’s art against that of her male contemporaries. The varied, intricate, and colorful visuals are enveloping, and I was captivated, at times.

Something of an modern art history tutorial, Lenz relies heavily on the voices of academics to outline Kusama’s place in the pantheon. Comparisons are made to Warhol, of course, and in one sequence, we learn that the great exploitative commercial artist may have gotten one of his ideas from Kusama. And because of this and other negative experiences, Kusama grew more and more paranoid, shutting herself off and diving into a kind of madness.

While we hear the voices of museum curators, critics, and gallery owners, the voice that is most impactful is that of the artist herself. Now in her late 80s, Kusama lives in Japan and is shown to be still creating. She cuts a striking image, as she dons a pink wig, wears bright colored clothing bearing patterns that may be taken from her art, and walks with a distinct shuffle. Given the money now paid for her work, it would be easy to dismiss this persona as one related to marketing and self-promotion. However, Lenz meticulously establishes this personality as part of Kusama’s history. It’s clearly not an act, as we learn that she lives in a facility that provides her with mental health support.

Above all, Lenz is able to show a transformation in Kusama from her early childhood to her days in NYC and through her present existence. This transformation is most visible in the expression on her face, which is now almost expressionless—a stare that hides frenzy. The archived footage and still images of Kusama from her New York days play in stark contrast to the Kusama today. But the art remains.

A colorful, radiant journey into personal obsession, “Kusama: Infinity” is part art history lesson paired with an examination of a life that toes ever closer to the abyss.