When I was invited to a screening of “The Artist,” I wasn’t that excited to hear that I had to sit through a silent picture. Sure, I had seen the standard canon over the years—films like “The General” that are available on Netflix. But the idea of making a film in a long abandoned format (in addition to being silent film, the aspect ratio is 4:3) seemed to me to be a shameless gimmick. Boy was I wrong. “The Artist” isn’t a gimmick film, but one that uses the silent movie technique as part of the narrative. Sound is used not only with the classic score but in critical places that I dare not spoil.

When I was invited to a screening of “The Artist,” I wasn’t that excited to hear that I had to sit through a silent picture. Sure, I had seen the standard canon over the years—films like “The General” that are available on Netflix. But the idea of making a film in a long abandoned format (in addition to being silent film, the aspect ratio is 4:3) seemed to me to be a shameless gimmick. Boy was I wrong. “The Artist” isn’t a gimmick film, but one that uses the silent movie technique as part of the narrative. Sound is used not only with the classic score but in critical places that I dare not spoil.

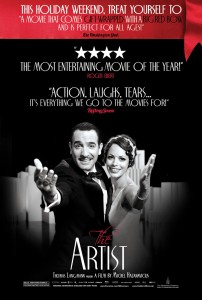

The story concerns a silent movie star George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) who, in 1927, is beginning to see the birth and growing popularity of talking pictures. Valentin, a gifted comic actor, and heartthrob, resists moving to sound roles. His wife (Penelope Ann Miller) is frustrated by his insistence to continue to make silent movies and eventually leaves him. Meanwhile, a young actress (played by Bérénice Bejo) who was given her break by Valentin becomes a talkie star. Can Valentin find redemption and make the move to talkies? The film chronicles his fall and possible resurgence.

Immensely entertaining, “The Artist” uses the silent movie technique brilliantly giving us a movie without actual sound dialogue but with a rousing musical score. After about 20 minutes, I adjusted to the form and engaged with the story and the characters. The two leads are perfect with Dujardin (best known for the “OSS 117” series) leading the way as Valentin. Although the silent technique works very well here, I doubt that the success of “The Artist” will spawn a host of imitators. And this is because the silent treatment was integral to the story. Making a silent movie about the end of the silent movie era makes perfect sense.

But creative use of silence was an important part of the best films of 2011. “Tinker Tailor” contains long stretches where it seems that Gary Oldman, playing spymaster Smiley, stared at other characters and uttered barely a word. And Michael Fassbender in “Shame” picked up girls merely by looking at them. Malick’s “Tree of Life” hardly featured one continuous conversation giving us bits of dialogue often in hushed whispers with muffled tones and surrounding the action with new age music videos about the creation of the universe. It was what was unsaid that told the best stories of the year. And relying on the subtext even where the actual text is lacking often produces the best cinema. Hopefully, films that give the audience more credit and make sophisticated points without spelling everything out will be lesson learned and carried forward from the down year of 2011 at the movies.

Jump back to the beginning.