Shannon’s limp is a constant reminder. Once he got in with the wrong guys. Bernie was one of those guys. He used to make movies, but that was before he figured out other less public ways to make a fortune. Nino is Bernie’s partner. He’s an aging tough guy with an inferiority complex. Shannon and Nino have a history, which carries some very bad memories. Irene doesn’t know any of these dangerous men. She’s just married to the wrong criminal. One day a mysterious man known only as the “kid” or the “driver” walks into their lives. He’s a man with no name, no past, and nothing to lose.

Shannon’s limp is a constant reminder. Once he got in with the wrong guys. Bernie was one of those guys. He used to make movies, but that was before he figured out other less public ways to make a fortune. Nino is Bernie’s partner. He’s an aging tough guy with an inferiority complex. Shannon and Nino have a history, which carries some very bad memories. Irene doesn’t know any of these dangerous men. She’s just married to the wrong criminal. One day a mysterious man known only as the “kid” or the “driver” walks into their lives. He’s a man with no name, no past, and nothing to lose.

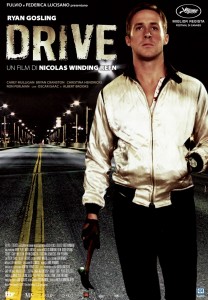

Director Nicolas Winding Refn’s “Drive” is already being heralded by some as a masterpiece, and it is easy to understand the exuberance for a picture this well-made. The movie opens with one of the smoothest pieces of direction I’ve seen in some time. The scene is a familiar getaway sequence but it instantly draws you in like the best modern crime movies. Comparisons to Michael Mann’s “Heat” will be made, but “Drive” is a much smaller film both in story arc and in character development. Unfortunately, “Drive” is also not as much fun as “Heat,” which will narrow its audience significantly.

“Drive” is a minor crime saga. It concerns a robbery gone wrong and how innocent people get caught in the crossfire. But the story-line is not as important as the style of the film. And the gritty 1980s influenced style adopted by Refn in “Drive” could start an underground trend.

Ryan Gosling plays the secretive role of Driver (yes, there is no name other than Driver given to the character). He has very sparse dialogue, but when he speaks, you should listen. At one point, he goes through his litany of rules as he offers his services to a criminal in need. The first time we hear these rules, they are cool. But when he repeats them to a jacked up wise guy, who could care less, they sound pretty lame. By repeating the same lines in two different sequences in practically the same way, but with subtle differences, Gosling shows us how talented he really is. The role of Driver is all about what he looks like, the dialogue is a very small part of it. Gosling plays the role with little expression on his face—it is as though he’s on a sedative. But small cracks in that façade shines through. Who is Driver? What’s his angle? The stoic performance by Gosling only deepens that mystery.

Some viewers will find the entire film pretentious to the extreme. And that view is completely fair. In fact, it may even be intended. Gosling moves almost in slow motion at times, methodically planning his next move—you can see the wheels turning. The criminals around him devour the scenery. Ron Perlman plays Nino as a familiar small-time gangster. Albert Brooks’ Bernie Rose is a fast-talking know it all, who is tired of the crime business, but has nothing else in his life. Bryan Cranston takes on the shady but good meaning Shannon from the view that with Driver on his team, it is okay to take dangerous risks again. Shannon’s mistake is in ignoring how his got his limp. All of these macho bad-guys act as the testosterone infused chorus in this tragedy and often speak for the largely silent and strong hero Driver.

Borrowing from the 1980s, director Refn crafts a terrific looking nostalgia piece. Although the story appears to take place in the present, it is really timeless. The title graphics and music reminded me of the work of Michael Mann and his 1980s television show “Miami Vice.” “Drive” also shares the same undaunting masculine edge and fascination with unlikely criminal types that Mann featured in one of his early classics “Thief.” Just as Mann cast grandfatherly looking Robert Prosky as the heavy in 1981’s “Thief,” Refn has Albert Brooks of all people playing the most dangerous villain in “Drive.” This kind of unusual casting makes the viewer instantly uneasy, because we’re not used to seeing someone like the neurotic Brooks play evil. And here Brooks fills the role so well that there is awards buzz.

It is easy to look at Refn’s work to date and say that his influences come from the Scorsese school. But with “Drive,” I was reminded of the films of one of Scorsese’s often collaborators Paul Schrader. “Drive’s” opening sequence felt a little like Schrader’s 1980 hit “American Gigolo” and the nighttime sequences in the city felt like Schrader’s forgotten gem “Light Sleeper.” Refn has the same feel for the dark underbelly of urban dwellers that marks the best crime films of the last 40 years. And “Drive” is best when it is setting up the story and introducing us to the players. Where it fails is in making us care about them enough to invest emotion in their ultimate fate.

“Drive” is not a film that a wide spectrum of viewers can enjoy. It is rated-R mainly for the violence, which is expected coming from the director of “Bronson” and the almost unbearably violent “Valhalla Rising.” But like those films, Refn is the kind of director that makes the bloodletting and visceral cruelty into an artistic experience. Narratively “Drive” is a meditation on violence and its consequences, using a pretentious story to make a metaphorical comment. And the view along the way is certainly worth the ride.