“Lincoln” is a fine film but not the one that most folks may have been expecting. Steven Spielberg opens his mini-historical-epic with a battle scene depicting African-American Union soldiers fighting white Confederate soldiers in the pouring rain. The soft blue images make all racial identities a bit muted but the powerful message is clear: “Lincoln” is less a film about the Civil War and more about race and our nation’s early struggle to end slavery.

“Lincoln” is a fine film but not the one that most folks may have been expecting. Steven Spielberg opens his mini-historical-epic with a battle scene depicting African-American Union soldiers fighting white Confederate soldiers in the pouring rain. The soft blue images make all racial identities a bit muted but the powerful message is clear: “Lincoln” is less a film about the Civil War and more about race and our nation’s early struggle to end slavery.

The story follows the title character in the waning days of the Civil War as he battles to gain passage of the 13th Amendment through the House of Representatives. The 13th Amendment, which was passed and ratified, officially ended slavery. At the time, Lincoln, a member of the Republican party, had a majority in the Congress but lacked the super-majority necessary in the House to get the Amendment passed by a two-thirds favorable vote. While the war raged and talk of peace circulated, Lincoln is depicted as focusing intensely on ending slavery in his time. The film brings us into the smoke-filled back room dealings and arm-twisting that eventually resulted in an end to slavery.

A quiet film, Spielberg works from a wordy script by Tony Kushner (“Munich”). I say “wordy” because the action involves constant orations often from the President. And while Lincoln may have been known for his public brevity, he was quite a spinner of yarns behind the scenes. At one point, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (Bruce McGill) says what many viewers might be thinking, something like, “oh no, here comes another story.” Spielberg and Kushner are fully aware of the kind of film they’re making—a quiet, focused, and intellectual movie instead of a loud and broadly pitched one. And some of the best moments in “Lincoln” show the President thinking and then pontificating and wrestling with how to respond to particular situations. It is almost a primer on critical thinking and the process of making decisions.

The intimate script smartly concentrates on small moral and internal conflicts played against the backdrop of the bloody Civil War. We get the fiery Representative Thaddeus Stephens (played by Tommy Lee Jones) railing against slavery and insulting his fellow Congressman without a moment’s thought or reflective repose. And these scenes contrast nicely with Lincoln’s folksy halting manner often prefaced with long stretches of pause prior the utterance of a single word. All this sets up the moment when the decision must be made and all talk tabled.

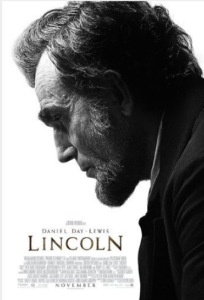

The performances are more than just the costumes and odd facial hair that often mars these historical flicks. Daniel Day-Lewis is his usual perfect self here adopting a unique and completely authentic accent and pinched body posture that one might associate with the Lincoln mythology. And the script gives him range from being presidential to being a father and a husband. Life in the White House has rarely felt more real.

But problematic is the sincere but flawed efforts of Sally Field, who is badly miscast at Mary Todd Lincoln. The major failing here isn’t Field’s work, which is very solid, but the fact that we clearly know that we are watching a 64 year old former movie star play someone 20 or so years younger. I read that Field gained weight for the role, and I can’t help but feel that this made her look even older. Again the script tries to explain this by mentioning that Lincoln looks 10 years older than when he took office, but one wonders why such a line should even be necessary. And while the war and the burdens of the Presidency do take their toll on the men and their spouses in office, I was unable to shake that Field was more convincing as the grandmother to the 9 or 10 year old child running about in the White House than his mother. Hats off to Spielberg for finding a prominent role for one of our favorite movie stars from year’s past, but for me, a younger actress would have sold the character better and not pulled me out of the narrative. Remember that there were reports that Liam Neeson was once slated to play Lincoln in this film but bowed out because he said he was “past my sell-by date.” Neeson would have been terrific in the role, but his instincts were probably spot on.

No matter what, “Lincoln” is a sharp and patient movie that compares well to other contemplative films seen in recent years. Like “The Social Network” or “Moneyball,” we step inside the process and explore it in vivid detail. And it is fascinating, especially if the various machinations on display are accurate. Naturally, Spielberg brings a bit of a sanctimonious tone to the affair, but these scenes don’t become too gratuitous. And let’s face it: the time and the issues are just too weighty to be handled in any other way than clear-eyed squareness lacking as much cynicism as possible. “Lincoln” is as good a film as could possibly be made about the passage of one of our most important Constitutional Amendments.