Was Mary Surratt innocent? She was the first woman to be executed by the U.S. government. Her crime was conspiring in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Was Mary Surratt innocent? She was the first woman to be executed by the U.S. government. Her crime was conspiring in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

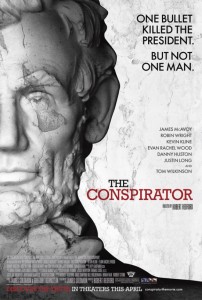

“The Conspirator” is a film that may be criticized as painting Surratt as a victim and the system that convicted her corrupt. But I didn’t see it that way at all, the central question concerning Surratt’s guilt is never fully answered in the movie. Sure, the draconian tactics following the assassination attributed to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton seem tyrannical and even sinister. The film, however, plays everything more objectively than most viewers would expect. The irony, of course, is that after her execution, Surratt’s son, John, was tried and not convicted in the assassination plot that resulted in his mother’s death by hanging. This fact should be lost on no one.

In the film, solemnly directed by sure-handed Robert Redford, Surratt is played skillfully by Robin Wright (see “Forrest Gump”). While she is certainly sympathetic, the tone of the award worthy performance and the approach taken by Redford manages to remove much of the melodrama that might otherwise mar any shot at credibility. I say “credibility” instead of accuracy, because I have no idea whether the film is historically accurate, but the movie sure feels credible. The time, post Civil War America in 1865, is captured in a way that makes it seem quaint and much less glamorous than we’ve been accustomed to seeing in Hollywood productions. The elitist parties shown in the movie are rather humble affairs lacking in pomp and circumstance. The scale of the entire production is rather small. Even the opening scene that takes place on a Civil War battlefield is restricted and shot closely conveying intimacy over the larger picture.

“The Conspirator” isn’t a historical epic, it is a courtroom procedural taken from a time when the Law as we know it wasn’t in place. The very protections we hold near and dear were still evolving and being interpreted on basic levels. Mary Surratt was not tried in any courtroom we are familiar with. Instead, she was tried and convicted in the assassination plot by a nine member military commission. And she was represented by a young attorney, Frederick Aiken, who was formerly a Union Army officer.

In the film, Aiken is played by James McAvoy (see “Wanted” and “Atonement”) who, at first, seems completely wrong for the role. In fact, McAvoy’s uncomfortable and uncertain attitude that one could characterize as “itchy” in playing Aiken is one of the reasons why the film’s second and third acts work so well. Aiken is depicted as not wanting to represent Surratt and being so new as a lawyer that his skills would be ill-suited for the task. But a little bit of magic happens as McAvoy literally grows into the role and we with him. It’s all part of the understated grace permeating Redford’s direction.

But as much as “The Conspirator” exudes sincerity, it is hardly an entertaining film. The early stages are slow going and some viewers will become restless. At times, it is like a Masterpiece Theater production languishing on dialogue heavy moments that lack action and suspense–the often necessary components of box office successes. But the slow elements made me admire the film even more. And there can be no doubt that but for involvement of iconoclast Robert Redford (now in his mid-70s), such a movie could not have found adequate funding. At least, in other hands, “The Conspirator” would have been given flashy epic treatment and been released into theaters in the winter vying for best picture honors. And that approach might have worked. It’s just that the movie that Redford’s made is one I’d respect more.

A handsome and important film focusing on one woman’s plight that reflects a nation’s division, “The Conspirator” reminds us that the big problems are often personal ones as well.