The legendary golfer Bobby Jones was quoted as saying that “golf is a game that is played on a five-inch course – the distance between your ears.” This is probably the reason why the almost mystical sport has not yielded many great movies. Filming what is going on in a golfer’s head has to be an almost impossible task.

The legendary golfer Bobby Jones was quoted as saying that “golf is a game that is played on a five-inch course – the distance between your ears.” This is probably the reason why the almost mystical sport has not yielded many great movies. Filming what is going on in a golfer’s head has to be an almost impossible task.

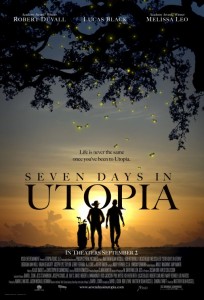

In “Seven Days in Utopia” aspiring professional golfer Luke Chisholm (Lucas Black) experiences a meltdown of epic proportions during a tournament. The meltdown is captured on national television making him a laughing stock. Even his father, who also serves as his caddy, turns his back on Luke. Wracked with despair, Luke aimlessly drives from the course only to have an accident in the dreamy little Texas town of Utopia. Now stranded, he meets the wise and kind Johnny Crawford (Robert Duvall), a former golf professional whose career ended badly. Maybe Johnny can help Luke find his game.

The problems with “Seven Days in Utopia” are too numerous to list. While the production is competent from a technical perspective, the narrative is hopelessly contrived. The relationship between Johnny and Luke lacks any sort of authenticity. The script, which is credited to four writers including the novelist, David Cook, who penned the source material, displays little comprehension of the mentor relationship. Johnny’s demons are long behind him. Luke’s demons are all around him. But while Johnny can help Luke, there is nothing that Luke can offer Johnny.

Mentorship is magical when the benefits are mutual. The best of these teacher/student relationships result in improvement and growth by both parties. And movies often capture the pathos of this symbiotic process vividly. “Good Will Hunting,” “Finding Forrester,” and “Antwone Fisher” are good modern examples. And even more recently “The Blind Side” proved that the familiar material can work in the religious/inspirational setting as well. “Utopia” fails to follow the examples set by those films. The mentor in the film, Johnny, does not appear to grow at all by virtue of his relationship with Luke. Such story telling is lazy, unsophisticated, and boring, and, sadly, “Seven Days in Utopia” is all of those things and worse.

Worse? How could a movie be worse than lazy and boring? “Seven Days in Utopia” actually concludes with intentional viewer frustration. We get a frustrating cheat of an ending that is as much a product of the technological age as it is the result of inexperienced, ill-advised filmmaking. This alone makes “Utopia” one of the worst films of this or any year.

Robert Duvall gets a pass for this one. His name and reputation probably helped get the movie made and will sell tickets. But when I spoke with him at the movie’s premiere, he told me that he made the movie because he likes to work. His response lacked passion. As a comparison, when I asked him about working with Billy Bob Thornton on the upcoming “Jayne Mansfield’s Car,” he was immediately enthusiastic and eager to say good things. Duvall’s attitude toward “Utopia” points up a telling truth about the movie: it lacks passion that could be shared with viewers.

One of the most surprising things about the film is that it screened for critics. “Seven Days in Utopia” is, after all, the “Fireproof” of golf movies. And like “Fireproof” the characters that populate the “Utopia” landscape are the product of an idealized Christian universe where no one uses expletives and sex is a mystery left to be discovered in the darkened safety of the bedrooms of married couples. And those couples are of the traditional variety.

There is nothing wrong with making a movie from a religious perspective. And many movies use Christian allegories in subtle and sophisticated ways. But in order for the message to carry any kind of weight, it must engage the viewer drawing him or her into a familiar world. And in that world people cuss and even kiss on the first date.