Don’t be intimidated by the complex nature of the espionage story told in “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.” It isn’t really about the intricate world of spying anyway.

Don’t be intimidated by the complex nature of the espionage story told in “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.” It isn’t really about the intricate world of spying anyway.

I wish I could take credit for the argument that “Tinker Tailor” isn’t about spying. The credit for that dubious and possibly tongue-in-cheek claim originated, at least, for me from British film critic Mark Kermode. Acting as a bit of a constant gadfly, Kermode has sparred with his listeners for more than a month about whether the film is really about spying. After finally seeing the movie, I think I know what he’s talking about. And I’ll give you my reasoning along with some arguments for the other side. If you free yourself from the idea that the film is a spy movie or about spying, you just might enjoy it more.

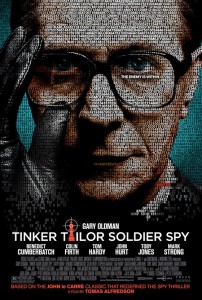

“Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” is taken from a famous novel of the same name from famed British espionage author John le Carré. le Carré is a former member of the British Foreign Service, therefore, it stands to reason that he would set a story about loyalty and betrayal in the world of secret intelligence organizations. le Carré writes what he knows about. His novel has been adapted before in 1979 in the form of a seven part mini-series for British television. The Oscar winning Alec Guinness was the star of that first adaptation. Readers certainly know the great English actor Guinness as Ben Obi-Wan Kenobi in “Star Wars.” But his work as le Carré’s chief protagonist named Smiley is more likely the kind of thing that he’d proudly point to on his resume. In the 2011 theatrical update, another talented Englishman Gary Oldman plays Smiley. And although Oldman has probably never delivered anything less than top-notch work, I have to say that I can’t imagine that he’s ever given a performance better than he delivers in “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.”

Oldman plays Smiley, who is a spy among spies, and second in command to Control (played by John Hurt). The secret intelligence service they belong to is often referred to as the “Circus.” There is a lot of double speak in this Byzantine narrative, as the title of which ought to provide some indication. When Control is pushed out of the Circus, he takes Smiley with him. The two men fade into virtual obscurity until one day following the death of Control, Smiley is retained by his government to investigate the Circus in a clandestine operation. The goal is to find the mole in the organization. But Smiley soon learns that his former mentor, Control, also suspected that Smiley could be the double agent. Therefore, everyone is a suspect and no one is safe. The hunt for the mole is on. And we aren’t given anything to hang our hat on—Smiley might actually be the one he’s been hired to ferret out.

So, yes, the plot involves the spy business and the world in which the action unfolds is gripped by the Cold War that was marked by secret agents and misinformation campaigns. There is a bit of a body count in the film as well, but don’t expect action on the level of a James Bond entry. In fact, in an interview I heard with director Tomas Alfredson, he spoke about wanting to “film” theater and give viewers a movie that was “long in and long out.” His point is that action thriller takes on the spy genre have often been short in and short out—entertaining thrills that don’t leave viewers talking about themes and issues for very long afterwards. And I think that this points up why “Tinker” works so well and is in fact a movie less about spying, if at all, and more about relationships between men and picking a side. Unlike slick and efficient action pictures, “Tinker” contains much more talk than probably any film set in the spy game ever made. There is a key scene where Smiley tells a story about attempting to induce a Soviet spy to defect that is fascinating and chilling and merely told by Oldman with no flashback scenes or even much score. Large portions of the film involve men staring at one another in soundproof rooms where they are endlessly tested. Sure, they are all spies, but the setting and their identities are secondary to the themes being explored.

Picking a side and staying true to one’s convictions is the heart of “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.” Mark Kermode is right. However, an argument to the contrary can be made as well. Without the device that spying provides, the tension that flows effectively through the film could never have been so securely maintained. Spying is critical to the film working.

An example supporting the “it’s about spying” argument involves one of “Tinker Tailor’s” subplots. Tom Hardy plays a spy named Ricki Tarr who becomes twisted by his ambition. While on a mission involving a suspected Soviet spy, Tarr becomes smitten with a beautiful woman. He deviates from standard operating procedure because he has become bored by his assignment and desires to move his status in the organization up a bit. He’s tired of doing the dirty work. But Tarr’s ambition backfires. And without the spy plot device and the mechanisms of the spy game, such a story would have been far less interesting. But once again, the key issue is loyalty and betrayal and less about the workings and techniques employed by spies.

You see, “Tinker Tailor” could have been set in the world of most any profession and ultimately not been about the profession, or certainly less about it, than about loyalty and cleaving onto one side. What matters here is making a choice and dealing with the good or bad consequences. In my mind’s eye, I can imagine this film directed by Kevin Smith and set within the world of mini-mart store clerks. While the stakes may have not been as high, the central themes involving divided loyalties could be effectively conveyed.

Finally, if you don’t think of “Tinker Tailor” as exclusively a spy movie, it might actually work better for you. A viewer less concerned with the geopolitical connections, Cold War politics, and historical accuracies can just sit back and study the characters and their motivations. Since the film is mainly a platform onto which so many gifted English actors are permitted to ply their craft, the underlying plot devices that provide the darker tension elements can be ignored entirely.

Many of my fellow critics commented collectively after seeing the film: what was that all about? Focusing too much on the intricacies of the plot could spoil the delights had in observing the actors emote at one another. To be exact, Oldman spends much of his time saying nothing and listening while others talk. John Hurt is menacing as Hell yelling quite a bit from a soundproofed trailer that is hidden within a nondescript warehouse. Colin Firth is his utterly charming self but is a suspect along with everyone else. And other actors like the diminutive Toby Jones get a chance to play top dog, while a tough guy like Tom Hardy shows a sensitive side under all that muscle. Fans of the BBC modern-set “Sherlock” series will be happy to see Benedict Cumberbatch as a lesser spy, and Mark Strong (from so many films these days including “Kick Ass”) shows a great deal of range. Not one performance is wrong, and the casting is as eclectic as it is perfect.

For director Tomas Alfredson, whose last film “Let the Right One In” has been said to be a vampire film, it appears that he’s intent on making movies that utilize familiar plot contrivances to comment about larger, thicker issues. Rather than getting bogged down in the details that develop complex plot devices, Alfredson is more concerned with relationships between people and how those relationships are formed, endure, and more often than not break down. “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” is a movie about loyalty and picking a side that just happens to be set in the world of spying.