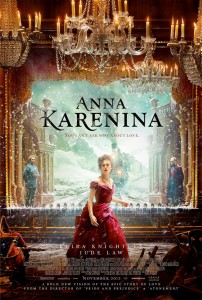

A feast for the eyes and for a time emotionally engaging, director Joe Wright delivers a unique take on the Tolstoy classic.

A feast for the eyes and for a time emotionally engaging, director Joe Wright delivers a unique take on the Tolstoy classic.

I heard an interview with Wright (the auteur of the marvelous Atonement) in which he explained why he decided to go so avant-garde with such familiar material. His reasoning, as I remember it, was that the story had been done before in a traditional, straight-forward way and he wanted his version to stand apart. And to that end, Wright does some interesting and, at times, magical things with the production. The action in “Anna Karenina” sometimes takes place on what appears to be an organic and evolving stage, while other scenes are on location—outside shots in a field are examples. This mix is dazzling early on, but as the film reaches the mid-point, the gimmick begins to wan and Wright seems to go away from his stage technique and focus on more familiar ones. Still, like “Cloud Atlas” early this year, the attempts to craft a unique and interesting visual are to be lauded and encouraged.

Sadly, while the visual style captivated me, at least, early on, the story quickly wore out its welcome. I found myself wandering, especially as the fantastic visual elements seemed to lessen. The performances, especially by Jude Law, are terrific and everyone is up to the tricky challenge of working within Wright’s complex and highly stylized environment. Keira Knightley attacks the flawed title character with adequate aplomb making Anna both pitied and despised. And Aaron Taylor-Johnson (“Kick Ass”) looks really lovely as the ill-fated Vronsky. In keeping with Wright’s visual flair, Vronsky is shot sumptuously showcasing both his opulence and his youth against that of Anna’s pathetic quest for love and happiness. Knightley and Taylor-Johnson are but five years different in age (with Knightley the elder), but Wright skillfully makes them appear more separated. This works well as Anna’s jealousy and paranoia about her younger lover’s affections are constantly examined and questioned.

The main problem with the narrative is that Anna comes off as really one note—a creature willing to give up her family for the love of a younger man. Central to understanding Anna’s dilemma is understanding the time in which the events are set. Not only was divorce an almost death sentence, but women were often the biggest losers, especially in social circles. The first half of the film explores this theme, but I did not find it followed up on as the film concludes. What’s left is poor Anna coming off as a selfish cheat. Certainly, many women viewers may see things differently. But for me I wanted a little more context rather than the easy explanation that Anna was mentally ill or that she was somehow a victim of love and the society in which she lived.

And I think, perhaps, Wright and his screenwriter Stoppard may intend to engender negative feelings toward Anna, especially as the film increasingly focuses on Anna’s young children. Telling is a scene in which a wet-nurse is seen clearly in the background following the birth of one of Anna’s children. This detachment (although appropriate for the time) instantly reminded me of another of this year’s frustrating movie female protagonists–Jackie Siegel from the documentary “The Queen of Versailles.” Viewers who have seen “Versailles” will remember Siegel’s flawed reasoning when she explains why she’s had something like seven children. Siegel tells us that when you can have nannies, why not have more kids?

But aside from my quibbles about the story, the visual style combined with top-notch acting characterizations makes “Anna Karenina” something truly different in the marketplace. Filmmakers, especially, will probably enjoy the style of it and excuse the story shortcomings.