Reverent and somber, Ridley Scott’s Biblical epic is a stale but handsome bore of a movie. The charismatic Moses deserves better.

Reverent and somber, Ridley Scott’s Biblical epic is a stale but handsome bore of a movie. The charismatic Moses deserves better.

Scott’s adaptation, written by four writers, is presumably based in part on the Old Testament, but an effort is made to abandon fantastical or unearthly elements in favor of more concrete explanations. The story begins with Moses (Christian Bale), a general in Pharaoh’s army, playing second fiddle to his rich kid cousin Rhamses (Joel Edgerton). The divide between them grows as Moses saves the prideful Rhamses in battle. Summed up best, Rhamses’ father Seti (John Tuturro) tells Moses that ironically he is more fit to lead but can’t due to rules of succession. And, as we all know, things get very complicated for Moses when it comes out that he might be a Hebrew.

There is no floating basket scene. We get the origin story in exposition—there’s a lot of talk in this film. And the accents vary greatly. Just think about the odd family assembled in “Exodus” in which Brooklyn born Tuturro is the father of Australian Edgerton with Sigourney Weaver playing mother—nobody really looks the part. It is fine to accept that the casting choices are some kind of homage to Hollywood of yesteryear, but I found the combination of these famous faces distracting. Scott is a director who probably could have made this movie without the stars albeit on a smaller budget. He could have put Egyptian and/or Jewish appropriate actors in key roles, but by glamming the whole affair up, he cheapens the material. The loser is Moses, an iconic historical hero who deserves better treatment. And themes of God and faith get papered over by spectacle.

Which brings us to the plagues? An effort is made to explain them and to a degree this is the most interesting part of the film. However, instead of a penultimate scene where Moses lays it all out for Rhamses, the characters talk privately, which cuts against the grandeur of the overarching narrative. In contrast, Scott does a good job visually showing us the progression of the plagues. Still, the events come abruptly and seem a little rushed. The action itself lacks emotional punch, as those directly affected are not developed with enough specificity for us to care about their suffering. The women in the film are barely introduced, underwritten is an understatement. And Moses is self-absorbed and arrogant, distant from the plagues, always busy trying to become Robin Hood (I’m not kidding) instead of peaceful messenger from God.

A bit of humor might have helped. “Exodus” is so serious that it makes you wonder whether the thought was that an ounce of laughter might have been considered disrespectful. Ironically, the humor that is introduced mainly through the Egyptian character Hegep (Ben Medelshohn) might be considered in bad taste. It’s also a little exploitive and broadly obvious playing on stereotypes.

Bale is miscast as Moses and this becomes clear in the film’s latter third when he is meant to age. The beard and white hair do not wear well on him. It looks fake, which is surprising given the budget and talent involved. And the entire ending of the film seems tacked on so that the story can roll to its familiar conclusion.

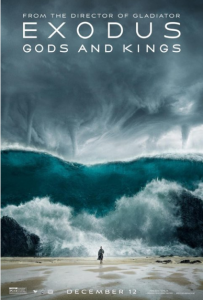

Without spoiling things, it is enough to say that Scott tries something new with regard to the parting of the Red Sea. I was not convinced by this approach and prefer the more explicit 1956 Cecil B. DeMille version. And this exposes the key problem with “Exodus:” why make the film at all? Was there some new ground to cover? Was there something that we all need to learn that DeMille was not able to do with his two versions (he made the film twice, once in 1923 and again in 1956)? Sadly, the answer is clearly “no.” The takeaway here is that the story seemed potentially profitable enough to make it a third time. Moses would not be happy.