Roman (Denzel Washington) talks in riddles throughout “Roman J. Israel, Esq.” And, sadly, solving any one of his brain teasers isn’t very interesting. Ultimately, Roman is an unlikeable, frustrating character in a film that has no idea what it’s about. Viewers will be confused and frustrated even as a valiant Washington tries in vain to make us care.

Roman (Denzel Washington) talks in riddles throughout “Roman J. Israel, Esq.” And, sadly, solving any one of his brain teasers isn’t very interesting. Ultimately, Roman is an unlikeable, frustrating character in a film that has no idea what it’s about. Viewers will be confused and frustrated even as a valiant Washington tries in vain to make us care.

Writer/director Dan Gilroy last gave us the edgy, subversive, and brutally entertaining “Nightcrawler” in 2014. And in that film, he centered his narrative around Louis Bloom (Jake Gyllenhaal), a weird and dangerous fellow whose goal was to get ahead in the freelance news business no matter the cost. In “Roman J. Israel, Esq.,” Gilroy takes a similar approach. Roman is a damaged person, whose life has been stunted by the strength of his well-meaning convictions. And it’s the well-meaning part that makes all the difference.

When Roman’s mentor and law partner falls into a coma with no expectation of regaining consciousness, the firm is taken over by the flashy George Pierce (Colin Farrell). Pierce’s goal is to liquidate and wind down the remaining cases and close the firm. Apparently, Roman isn’t a partner at all. He fashions himself the brains behind the firm, but for some reason that is really never explained, Roman has no legal right to take his half of the practice and move forward. The explanation may be related to Roman’s mental disability, although we’re never given any information from which to understand his disorder.

Recognizing Roman’s talent, George tries to hire him, calling Roman some kind of “legal savant.” At first, Roman resists, and for a time, he unsuccessfully tries to find work. In one scene, Roman attempts to get a job at a Civil Rights non-profit only to be informed that the organization is made up of volunteers. This inevitably leads him back to George where he will be faced with decisions that warp his moral compass.

Frustrating is the word here. By playing fast and loose with the law, Gilroy’s script features a combination of black letter legal principles and Hollywood legal fantasy. While I’m not licensed to practice in the State of California, where this film takes place, I can’t imagine that the phrases used by Roman are legally accurate. But this doesn’t matter, because for a while, the narrative trades uncomfortably on Washington’s odd performance.

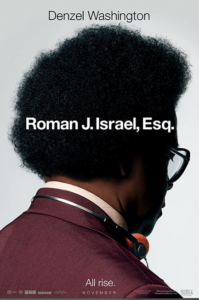

Odd defines Washington’s acting choices here. Clearly having gained weight for the role and adorned in what appears to be thrift shop clothing, Roman is one of the most unappealing heroes to recently lead a wide release. There would be nothing wrong with an unappealing hero had the script given the viewer a way into his particular brand of weirdness and made us understand him. Instead of telling us why Roman acts the way he does or provide us with a glimpse at his backstory, the narrative is more interested in plot leaving character primarily to Washington to craft through a series of almost unintelligible mumbling rants.

But unlike the uncompromising darkness that drove Louis Bloom in Gilroy’s “Nightcrawler,” Roman is at heart a good guy. And throughout the movie, Roman carries around a large brief case that he says contains a brief or filing of some kind that he claims will change the criminal justice system for the better. Since such a thing either does not exist in real life or would be too difficult to actually describe in a movie, the document, ultimately shown as a stack of papers, acts as the McGuffin, which merely provides some minor artificial solace in the film’s closing moments.

And with regard to that mysterious stack of papers, I thought of Prof. Grady Tripp, who was played by Michael Douglas in the late Curtis Hanson’s fantastic 2000 film “Wonder Boys.” You see, like Roman, Grady has for years been working on a huge filing that spans hundreds, if not thousands of pages. But in “Wonder Boys,” we come to understand that that massive exegesis is what holds Grady back from having a real life. The same thing is clearly at work in “Roman J. Israel, Esq.,” but the script falls into crime cliche where it should be focused on one man’s moment of clarity that his well-meaning intentions were misplaced.

Instead of embracing darkness and obsession like he did marvelously in “Nightcrawler,” Gilroy wants to redeem Roman and make us all feel good. It just doesn’t work. Since very few of us could actually relate to Roman, we don’t care enough about him nor do we understand enough about his confusing motivations to engage with the story or the character. This makes “Roman J. Israel, Esq.” a disappointing missed opportunity.