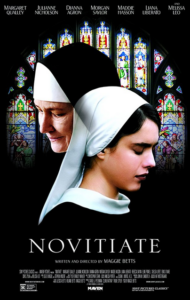

An astonishing narrative feature debut for director Margaret Betts, “Novitiate” takes the viewer into a place only either romanticized or demonized in previous films. This intimately shot and told tale is a must see for anyone questioning their faith in God or anything that demands sacrifice for admission.

An astonishing narrative feature debut for director Margaret Betts, “Novitiate” takes the viewer into a place only either romanticized or demonized in previous films. This intimately shot and told tale is a must see for anyone questioning their faith in God or anything that demands sacrifice for admission.

When Cathleen (Margaret Qualley) embraces Catholicism it makes sense for her to become a nun. Her mother Nora (Julianne Nicholson) was never religious but exposed her daughter to the Church at a young age. Eventually, Cathleen was awarded a scholarship to a Catholic school, which started her religious education. But once her journey begins toward becoming a nun, the harsh reality of what it takes to bond forever with God furthers a new awakening.

“Novitiate” takes place from the 1950s into the ‘60s and is set predominantly within the walls of a convent. While we’ve seen nuns on screen for years, few films feels as authentic. Of course, I have no idea whether what we see on screen is accurate, however, it sure feels real.

Led by the oppressive Reverend Mother (a perfect Melissa Leo), we learn that the convent’s leadership is struggling with the dawning era of Vatican II, which will loosen things up significantly. The Reverend Mother is naturally threatened by the changes, especially when she reveals early on that for something like 40 years, she’s not left the convent’s walls. Having been schooled in the ways of the Church, the nuns know only an unyielding commitment to restraint. No room is made for the pleasures of the flesh. Many younger nuns struggle greatly to overcome natural yearnings, which sometimes manifests itself in feelings for one another.

A quiet and methodical narrative, “Novitiate” requires patience, but the reward is great. Certain scenes are heart-breaking. Surprisingly, even the vicious Reverend Mother is sensitively handled as the shattering Vatican II announcement is finally made. Everything that provides the basis and structure for their convent is changed and not only are their foundations shaken, but the grip they have on the younger sisters in-training is endangered.

There’s a moment in this film when the young sisters dance around a bonfire. They have just reached a stage in their religious education that required them to don wedding dresses and pledge themselves to God. Their faces are glowing before the fire and they happily dance. While the institution as it then existed was based on suppressing one’s carnal urges, the girls look truly happy. Betts, who both directs and writes here, appears to get that moment and others exactly right. There is joy in one’s relationship to God, and regardless how cynical we can become, this commitment cannot be easily dismissed.