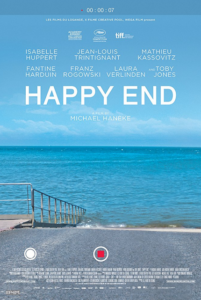

When Michael Haneke (“Caché,” “Amour”) writes and directs a movie about a dysfunctional family, calling the result “Happy End” has to be some kind of cruel joke. A keen observer of the darker side of the private lives of people in positions of authority, Haneke frustrates and confounds, while also exposing seminal truths. And “Happy End” is a minor addition to his painful and mournfully brilliant canon.

When Michael Haneke (“Caché,” “Amour”) writes and directs a movie about a dysfunctional family, calling the result “Happy End” has to be some kind of cruel joke. A keen observer of the darker side of the private lives of people in positions of authority, Haneke frustrates and confounds, while also exposing seminal truths. And “Happy End” is a minor addition to his painful and mournfully brilliant canon.

When Eve Laurent’s troubled mother is hospitalized because she’s been “poisoned,” she’s forced to move in with her father, Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz). The adjustment for her is difficult—new school, no real bedroom in his apartment, and even a new little brother and step-mother. But Eve (a fantastic Fantine Harduin) isn’t a normal girl, she’s had to deal with all kinds of disappointment and depression her entire short life. When asked how old she is, Eve insists that she’s thirteen even though she’s still twelve. Growing up fast and quickly becoming an old soul too soon is a major theme here.

While Eve is making due in a new space, the Laurent family is coping with a business crisis. Haneke makes excellent use of security cam footage to set this stage for a major event that hangs like a pall over the entire story. The family business, a construction firm, is in the control of Anne Laurent (Isabelle Huppert), who is struggling to balance her obligations to the company with her duty to her family. The family’s once powerful patriarch Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) has become obsessed with ending his life. Inevitably, this brings him closer to his granddaughter Eve. And while Anne is managing Georges in decline, she has to face her son’s mental health problems.

There are moments in “Happy End” where you wonder whether Haneke will go easy on us and deliver something manipulative and familiar. But no such luck. While this isn’t as dark as some of his other films, and dark isn’t really fair, this is a movie that tells truths, some of them in the open, and others only spoken of in whispers. And in exposing these hidden truths, it is the way that Haneke makes use of the camera that intimately informs the viewer as to the narrative beats.

Working once again with cinematographer Christian Berger (whose work is really impressive, see “The White Ribbon,” and the marvelous “Cache”), Haneke only moves the camera when he’s telling us something important. He raises and lowers the camera when he’s hinting at perspective forcing us to move with the character—putting us directly in that space. And he uses various formats and aspect ratios, including expert utilization of disturbing cell phone video. What is really special is how Haneke and Berger, both veteran filmmakers well into their 70s, take risks with new technologies and make those choices part of the fabric of the story itself. It is their experience and patience that makes the digital technology less a gimmick and more of a key narrative device.

To be fair and as a warning, watching a film from this marvelous director and cinematographer combination has become an exercise in emotional endurance, because sometimes the events get so frustrating, you may want to stop watching. Note that “Happy End” is 107 minutes in length. Compare it to another foreign family drama 2016’s “Toni Erdmann” that clocked in at a mammoth 162 minutes, and this film seems positively breezy.

Thankfully, Haneke doesn’t pull an Alexander Payne, and he hasn’t succumbed to pressure to make something like “Downsizing.” There is a place in cinema for Haneke, and yes, Payne’s particular flavor of nihilism. And where Payne gave us “Nebraska” a few years ago, Haneke gives us an equally close to the bone, hard-hitting family drama in “Happy End.”

But what’s missing is a little of the surreal comedy that make the films of Luis Buñuel (“The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie”) so much fun to watch. If Haneke decided to retain his signature bite and insert a bit more humor, we’d see a broader audience for his work. But at what cost? Haneke is a truth teller, and the truth is often ugly and not very funny.