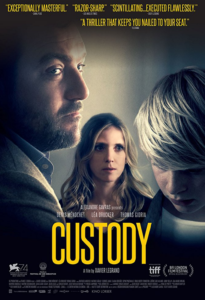

A devastating, authentic portrait of divorce and obsession, writer/director Xavier Legrand’s debut feature is a stunner.

Miriam Besson (Léa Drucker) has had it with her husband Antoine (Denis Ménochet). In a divorce hearing, we learn that the couple have two children Joséphine (Mathilde Auneveux), age 18, and the young Julien (Thomas Gioria). Letters are read from the children, both of which express a desire to not see their father. Violence is alleged. However, Antoine’s attorney is able to point out that the allegations of abusive behavior are not supported and are out of step with his public persona.

Miriam Besson (Léa Drucker) has had it with her husband Antoine (Denis Ménochet). In a divorce hearing, we learn that the couple have two children Joséphine (Mathilde Auneveux), age 18, and the young Julien (Thomas Gioria). Letters are read from the children, both of which express a desire to not see their father. Violence is alleged. However, Antoine’s attorney is able to point out that the allegations of abusive behavior are not supported and are out of step with his public persona.

The judge agrees with Antoine and grants visitation with Julien. Joséphine is 18 and can no longer be compelled to visit with her father. It’s the visitation that worries Miriam.

Determined to keep Antoine away from her, Miriam changes her cell phone number, keeps her apartment address a mystery, and refuses to even speak with Antoine. Naturally, this frustrates Antoine, who is passionately intent on being a part of his son’s life. And in light of Antoine’s sincere efforts to visit, Miriam’s actions are suspect. Is she alienating the children from their father out of personal animus?

Determined to keep Antoine away from her, Miriam changes her cell phone number, keeps her apartment address a mystery, and refuses to even speak with Antoine. Naturally, this frustrates Antoine, who is passionately intent on being a part of his son’s life. And in light of Antoine’s sincere efforts to visit, Miriam’s actions are suspect. Is she alienating the children from their father out of personal animus?

Part of the magic of filmmaker Xavier Legrand’s film is that it keeps you guessing. It challenges you not to take sides. By holding back and giving us very little of the past, the tension builds as we struggle to understand. Antoine is a slowly boiling pot, and his initial reactions to Miriam’s secretive campaign against him are understandable. He’s being shut out from his family. It doesn’t seem to be fair.

Julien is constantly in a state of shock. He trembles around his father, who calls him “Sweetie,” hugging the boy with affection. What does Julien know that we don’t?

As Julien, the young Gioria displays terror both inside and out. This little actor is remarkable, and his terrified performance allows Antoine to simmer. Their father-son relationship, although strained, is credible—a familiar chemistry that works. Children don’t always like their parents, and sometimes, they fear them. This isn’t necessarily abuse, but here we wonder.

“Custody” is a patient film, but it never seems slow or a labor. Part of the effectiveness has to do with the calm camera work by cinematographer Nathalie Durand. Durand, who lensed Roger Michell’s fun “Le Week-End,” never reminds you that she’s working. We get long shots where things are revealed instead of shown to us by a cut and lens change.

For example, we learn key details about Joséphine, as she secrets herself in a school bathroom stall. One scene has Miriam and Julien huddled together in a dark bedroom, and importantly, their eyes just catch the light, which is a tricky shot to get right. It’s the tiny details that matter here, because this is a mystery that challenges us to be objective. We’re unraveling this mystery by paying attention to what is shown to us as much as what we hear said. This is why a calm, restrained camera, that doesn’t get in the way, is critical.

Family struggles and attempts at civility are universal themes. “Custody,” is a French film, but, as an American father, who shares custody of a teen daughter, I instantly related to it. This kind of frustrating family drama reminded me of that Oscar winning Iranian film “A Separation.” These movies give international audiences a peek into foreign (or thought to be) domestic lifestyles and demonstrate how similar we all are. “Custody” makes us feel the personal vexation of loss and the inability to move on.