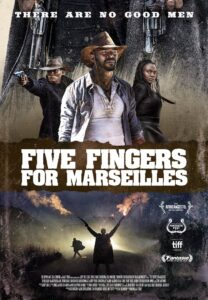

“Five Fingers for Marseilles” brings a fresh modern take on the spaghetti western to post-apartheid South Africa.

On the surface, “Five Fingers” tells the familiar story of an isolated town under the thumb of a violent warlord put in place by weak political leaders. The backstory concerns five friends who are pulled apart when one of them, Tau, stands up to corrupt authorities. Twenty years later, after Tau (Vuyo Dabula) has transformed into the infamous criminal called the Lion, he returns to his home town in hopes of living a quiet crime free life. Of course, when he discovers that an evil warlord has set up shop there and has been empowered by one of his old friends, Tau must help bring justice to a town living in fear. This sets him up on a collision course with the evil warlord and a chance at redemption for anyone willing to do the right thing.

On the surface, “Five Fingers” tells the familiar story of an isolated town under the thumb of a violent warlord put in place by weak political leaders. The backstory concerns five friends who are pulled apart when one of them, Tau, stands up to corrupt authorities. Twenty years later, after Tau (Vuyo Dabula) has transformed into the infamous criminal called the Lion, he returns to his home town in hopes of living a quiet crime free life. Of course, when he discovers that an evil warlord has set up shop there and has been empowered by one of his old friends, Tau must help bring justice to a town living in fear. This sets him up on a collision course with the evil warlord and a chance at redemption for anyone willing to do the right thing.

Director Michael Matthews and screenwriter Sean Drummond get all the Western genre elements right, relying appropriately on the beats and the look associated with a classic Sergio Leone production lensed by the great Tonino Delli Colli. This makes “Five Fingers” an often meditative affair punctuated by moments of stylized violence. But the setting, time-period, and language (which includes sparing bits of English together with native tongues) help kick the entire production up a notch.

The beautiful cinematography from relative newcomer Shaun Lee is a major standout. We get widely shot, gorgeous vistas, dramatic closeups, and well captured night shots. Color is vividly saturated with high contrast that accentuates the stark, rough environment. Composition is straight from the best Westerns of the genre. And while the time is modern, some years after the end of apartheid, which officially terminated in 1994, “Five Fingers” could easily be a part of the Leone Western canon.

Sean Drummond’s script is layered and requires some attention to follow. Tau is a sullen soul and his relationship to those around him very strained. The presence of the warlord has everyone on edge. The land itself, cracked, largely barren, sun-baked appears without sympathy. Onto this canvas, Drummond takes time to set up who all the characters, which slows the narrative. This careful development elevates the movie above a run-of-mill actioner. “Five Fingers” is about friendship and justice and the effect that youthful decisions has on a person’s later development.

Because the performances are uniformly committed and sincerely delivered, the elevated level of melodrama never seems forced or wrong. Admittedly, the, at times, overly heavy story could have used a bit of dry humor. However, such a tonal shift would have been tricky. Don’t expect the hero to have a choice one-liner, as he doles out a particular brand of justice.

The action sequences, which often end in violent, bloody death, don’t linger on the carnage or glamorize the events. Gunplay seems to be realistic—no quick draws, no magic shots, or outlandish shoot-outs. However, there is one extended gun battle that is well-constructed in how it avoids typical action tropes. No one holds a gun superficially or does an athletic roll while firing off accurate shots. It’s understandably messy.

And when characters are shot many times, they don’t immediately die, rather, they continue to fight awkwardly, often meeting their end in not so neat and tidy ways. You get the impression that the townspeople will be carefully cleaning up the bodies that litter the streets. There is a sense of community and weight built into the authentic production that makes “Five Fingers” more of a dramatic action picture and less a modern shoot-em-up.

“Five Fingers for Marseilles” is an excellent introduction to a filmmaking team led by Michael Matthews in an impressive directing debut.