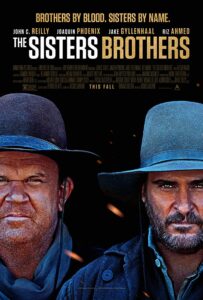

French auteur Jacques Audiard (“A Prophet”) makes his English language debut by delivering a sublime take on the classic American Western.

The Sisters brothers are Charlie (Joaquin Phoenix) and his older sibling Eli (John C. Reilly). To put it bluntly, they kill people. And they aren’t bad at it. As hired guns in 1850s Oregon, they have come into the employ of the Commodore (Rutger Hauer), a shadowy gangster of sorts, who uses the brothers as his chief enforcers. And enforce they do, with often murderous and bloody results. It’s all very messy, but in the lawless West, the brothers are unrestrained.

The Sisters brothers are Charlie (Joaquin Phoenix) and his older sibling Eli (John C. Reilly). To put it bluntly, they kill people. And they aren’t bad at it. As hired guns in 1850s Oregon, they have come into the employ of the Commodore (Rutger Hauer), a shadowy gangster of sorts, who uses the brothers as his chief enforcers. And enforce they do, with often murderous and bloody results. It’s all very messy, but in the lawless West, the brothers are unrestrained.

When the Commodore sends them out to hunt and likely kill Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed), the brothers embark on horseback through mountainous terrain and several developing towns. Warm, a chemist, has come up with a concoction that will make finding gold infinitely easier. Before killing Warm, the brothers are to extract from him the formula. Ahead of them, the Commodore has dispatched John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), a learned detective. Morris’ job is to locate Warm and detain him until the brothers arrive and finish the job.

But when Morris encounters Warm, he’s immediately taken with him. A small, soft spoken, thoughtful man, Warm’s ideas, centering around establishing a utopian society, make a whole lot of sense. And in the dangerous world that they inhabit, finding a peaceful place to live could be Morris’ salvation.

“The Sisters Brothers” is one of the best Westerns I’ve seen in some time. Recently, there’s been a return to this vintage genre with uneven results. Earlier this year, the Zellner brothers brought their tilted stylings into the 1870s with “Damsel,” starring Robert Pattison and Mia Wasikowska. And in 2015, John Maclean wrote and directed the excellent “Slow West,” starring Kodi Smit-McPhee and Michael Fassbender. Hot off his campy success with the wildly over-the-top Western “Django Unchained,” Quentin Tarantino gave us 2015’s “The Hateful Eight.”

Those films brought some modern sensibilities into the the Old West narrative, an approach often referred to as the “revisionist Western.” In the 1960s and 1970s, filmmakers began questioning traditional thought in the genre. The attempt was a step away from the squareness associated with the work of John Ford, for example, and to endorse drama and comedy that more realistically (or modernly) depicted the rough lifestyles of the time.

In the modern Western, no longer were there clear distinctions between right and wrong, rather, the motivations of the players were considered more intricately. This was consistent with modern evolving beliefs that tried to avoid prejudice and stereotypes and demonization of particular groups. History was being reevaluated in light of this new thinking. On screen, it went way beyond graphic displays of violence, sex, and the plentiful use of the f—- word, although these elements were important components of this sub-genre’s development.

“The Sisters Brothers” follows in this possibly revisionist direction, as the brothers grapple with their decisions and the need to leave the violent life. They are two terrible men, and for reasons I dare not spoil, possibly unredeemable. But the screenplay, written by Auidard and his collaborator Thomas Bidegain, manages to make these horrible men likable, even endearing. And this happens despite the fact that the anti-heroes are merciless killing machines.

It helps that the brothers are played by John C. Reilly and Joaquin Phoenix, two gifted actors. While Phoenix can be hard to warm up to, his pairing with the perpetual everyman Reilly is wonderful. And although they don’t really look like brothers, almost instantly, you don’t question their relationship. Playing the older sibling Eli, Reilly is the calmer, wiser of the duo. He’s always protecting the impulsive but more intelligent Charlie, even if that means doing bad things, like killing, that would otherwise be against his nature. Eli might be a good person, while Charlie may not be. Of course, the concept of good and evil is relative in a place and a time in which law and justice are constantly in flux. This moral relativism is on display throughout the film.

The West is captured by veteran cinematographer Benoît Debie, who often works with Argentinian filmmaker Gaspar Noé (see “Irreversible” and others). Using the Alexa Mini and Alexa XT digital cameras, Debie is restrained, keeping the camera calm, and movements minimal—nothing is distracting. The look is soft and rather light blue, without the hint of something like a Technicolor high saturation. Skin tones share this light blueness, but appear very natural. It’s an impressive choice, because this is a film filled with carnage, and the softness of the image makes for a nice contrast.

Even though the thrust of the story is very heavy, and the violence abundant, “The Sisters Brothers” is also funny and biting. The comedy naturally evolves fitting the otherwise horrific moments. For example, in one scene, the brothers kill someone and then are confronted by what appears to be an angry mob. Eli is designated to say something, but since he’s a simple guy, his words are less than eloquent. But they are true and necessary words, exactly right for that instant. And it is Eli, the emotional center of the film, who has to say them.

“The Sisters Brothers” explores the intersecting themes of fellowship, brotherhood, and friendship in a sustained and compelling way. The relationships develop meaningfully throughout the story. As Morris grows closer to Warm, with Eli and Charlie on their trail, relationships are tested and strained. Morris and Warm share a deep platonic bond, it’s really lovely. And Eli is forced to keep Charlie from allowing his worst impulses to overcome him. It’s touching how true and loyal Eli is to the people and animals in his life that he trusts. Reilly, with his big baby face, oafish mannerisms and awkward gait is absolutely perfect for this role, which might be his best to date. In a movie with four leading men, Reilly is the standout, the star, and should be recognized for his work.

Audiard and his writing partner Bidegain obviously make a good team. And here they marvelously adapt a novel by Canadian writer Patrick DeWitt. It’s surprising how this international combination manages to comment about the American experience in such an authentic and impactful way. “The Sisters Brothers” is one of the year’s best films.