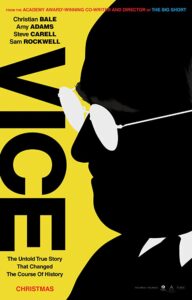

Christian Bale delivers an award-worthy performance as Vice President Dick Cheney.

With “Vice,” the spirited, stunt director Adam McKay, who brought his energetic brand of filmmaking to “The Big Short” in 2015, tackles a singular, infamous subject in the former Vice President Dick Cheney. This time around, the film is more focused, but ultimately will have conservative viewers frustrated, especially as the characterizations of significant Republican figures tips over into outright parody. “Vice” is a movie that will play best to already converted, folks who never had any respect for the mercurial Vice President, or worse, always despised him.

McKay’s take on Cheney’s life follows him from his boozing college years through his time in the White House. We meet the future, shadowy leader (played with uncanny commitment by Bale) at a very low time in his life. After flunking out of an Ivy League and being arrested for driving under the influence, his wife Lynne (Amy Adams) lays down the law—get sober, get a career, or she’s leaving. It works, and Cheney reshapes his life around a new ideology, which politics aside, driven by Cheney’s unique talent for discretion. The guy is a low talker—a political whisperer.

McKay speculates as to Cheney’s early motivations, leaving us with the impression that his political philosophy is the product of ambition and luck, rather than deep-seated conservative beliefs. However, there is a point when Lynne takes over one of the early campaigns and demonstrates what the two believe, regardless whether it is politically correct.

The mercenary side of politics does rear its ugly head, however, when they are confronted by their daughter’s sexual identity and positions on gay marriage. It’s this part of the film that seems a little forced. Allison Pill is well cast as the Cheney daughter Mary. But she’s depicted as all weepy emotion, flailing her arms and shedding tears that sink deep into the Vice’s heart.

The problem with this part of the narrative is that it’s played largely for one hypocritical moment in the film involving older sister Liz (Lily Rabe), who’s running for Congress. When the uncomfortable decision to oppose gay marriage is made, it will enrage viewers. But I thought immediately that there is no real way to know exactly how this gut-wrenching decision actually went down. Was it the Vice that made the final call?

Given Lynne’s overarching presence in guiding his career in politics, I suspect that the women in his life were more a factor in how he made decisions than anyone else. McKay gives us this concept in scenes involving Lynne, but the children are shown as bratty and one-note. There is a moment in the situation room following the events of 9/11 in which we see Lynne touching her husband for support—the two made an imposing team. McKay grants the Cheneys that moment, but his complete distaste for their ideology on every level permeates the entire film—infecting it with a slant that must be accepted for the movie to work.

I suppose that understanding a man that is so very private and insular was next to impossible for McKay, who both directs and writes here. He does his best from his perspective, however, his handling of facts is clearly clouded by liberal ideology. And to his credit, he acknowledges this in an end credit epilogue that is both self-aware and funny. Reaching for the humor in what is an otherwise weighty historical footnote is McKay’s masterstroke. And “Vice” proves to be hugely entertaining, provided, however, that you don’t take the film as a history lesson. This isn’t meant to be a documentary, rather, it’s a narrative film influenced by real world events.

But is “Vice” parody or something else? Casting is of the stunt variety. Steve Carell, who was so good in “The Big Short,” returns to work with McKay here playing Donald Rumsfeld. It’s not a performance that casts the former Secretary of Defense and former White House Chief of Staff in a favorable light. Carell is positively tweaked, almost to a cartoonish degree. Like others in the film, he has been made to look the part, but the substance is constantly on the edge of being one big joke.

And the parody aspect is approached as well with Sam Rockwell’s turn as George W. Bush, depicted as completely clueless. Rockwell certainly has the look of the former president down, but everything about the performance is exaggerated. The typical Bush mannerisms lean toward SNL great Dana Carvey’s impersonation of W’s father, and none of it is the least bit flattering. McKay’s commitment to his jokey, energetic form of filmmaking prevents him from deftly giving sentimentality to the subjects with whom he dislikes. It’s almost a complete lack of empathy, in which he’s bailed out by the central performance—a moment when Bale bows his head in disgust, demonstrating shame in the only way the very private man could. Regardless, there’s no doubt that he has little love for Cheney, Bush, and certainly not Rumsfeld.

One thing is clear, McKay takes advantage of the sandbox he’s been given by Hollywood. A similar approach that skewered President Obama, for example, would not likely find funding for feature motion picture treatment. Humor in cinema apparently belongs to one side of the political aisle, and McKay knows it.