The banal humor of “Little” fails to take advantage of its super-talented cast.

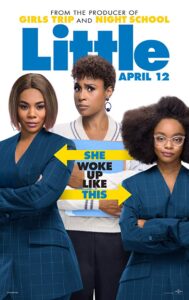

Knowing what you know now, if you could, what would you change in your past? Not much is the answer that we get from the wholly derivative “Little.” The talented threesome of Regina Hall, Issa Rae, and Marsai Martin deserve better. This lazy and only sporadically funny film has dragon lady, tech entrepreneur Jordan Sanders (Hall) magically reverting to her former tween self (played by Martin). Perhaps the best thing about this transformation is the character’s great hair that is like some kind of wonderfully natural special effect. Watching that fantastic hair dominate her tween head so charmingly almost makes up for the missteps that follow.

Tell me you’ve seen this one before: a grumpy, unpleasant, cut-throat executive goes to sleep one night and wakes in the body of a 12 or 13 year-old. But despite the physical change, she still possesses the mind of her older self. Her dutiful, but stepped-on assistant, April Williams (Rae), suggests that this is a chance at a do over. After watching this barely passable feature motion picture, director Tina Gordon Chism (“Peeples”) might want a do over as well.

It should come as no surprise that Chism, who also received a co-writing credit here, wrote the screenplay for “What Men Want” released earlier this year. That film, which was a re-imagining of the 2000 Nancy Meyers film “What Women Want,” has an eerily similar shape to “Little.” Both films recycle formerly successful film ideas with diminishing returns. But where “What Men Want” wore its “R” rating well and delivered some raunchy laughs, “Little” goes the other way and ultimately wallows too much is cheap sentimentality.

Like “What Men Want,” “Little” is a clear re-imaging of a popular Hollywood property, even if it fails to credit Penny Marshall’s Oscar nominated 1988 film “Big.” The somewhat modern approach taken by Chism is to abandon development of the fantasy elements in favor of cutting to jokes and slapstick. These films trade extensively on built-in audience knowledge of the world created by previous cinematic entries. And in spending little or no time on the magic involved (there’s no Zoltar in “Little”), we get lackadaisical story-telling that is woefully missing key narrative pieces that credibility endear with viewers the characters and their wacky fate.

For example, Sanders (played with much energy by Regina Hall) is informed by her biggest client (a ridiculous, but note-worthy Mikey Day) that unless she can come up with a stellar new app idea in 48 hours, he’s taking his business elsewhere. This leads to a confrontation with her staff in which she berates them both emotionally and physically.

This scene should have been a “Glengarry Glen Ross” moment. My reference to the James Foley adaptation of the famous David Mamet play (Mamet, also, wrote the screenplay, of course) is meant to remind viewers of the virtuoso sequence in which the sales team is given an ultimatum by a character named Blake (a scene-stealing turn by Alec Baldwin). In a brutal speech, that today might run afoul for its political incorrectness, Blake explains that the top salesman gets a Cadillac Eldorado, second, a set of steak knives, and third, gets fired.

If you’re going to steal from the past, why not steal from the best, right? So, instead of a “Glengarry Glen Ross” type drubbing of her employees, we get an inane, unfunny, and criminally abusive spiel by Sanders that is so leaden that it’s hard for the movie to recover. This is one of many completely wrong-headed scenes that permeate the film.

Another problem is that the way the story is presented it’s hard to buy Sanders as the head of a technology company. The workplace, that features huge posters of Sanders gracing the covers of major magazines, doesn’t seem like a place where anything significant is created. And the way in which the characters appear to be working does not instill viewers with any sense that they are looking at a successful company that makes apps. Ultimately, this throwaway part of the film is about as real as when Mark Wahlberg played the frontman of a major rock band in 2001’s “Rock Star.” One wonders if Chism researched the app business prior to penning the script with Tracy Oliver. While choosing another business would not have been as sexy, it might have helped if we believed, at least, partially, that the protagonist really was a big-time tech executive.

It’s all a darned shame, because Rae and, especially Martin are some of the freshest faces working today. There’s chemistry between these two, but they are given nothing of substance to work with. At times, Rae appears to be winging it, especially during one excruciating moment in which they perform an awkward, spontaneous duet in a restaurant. So much here fits the definition of wince-inducing.

But all is not lost. Martin has some fun, playful moments as her character adjusts to life in the body of her tween self. And Rae’s initial setup featuring a spacious apartment (showcasing Atlanta’s affordability) and a very cool looking bicycle are interesting, hinting at a hip, more sophisticated story. The infectious Rae, who is just so natural on screen, needs a better vehicle. At least, Atlanta gets to play itself here, which is becoming more common. And the city looks great.

Taking advantage of the collective goodwill generated by the films of the past, namely “Big,” “Little” fails to find the magic that made us think introspectively about what happens when innocence is lost.