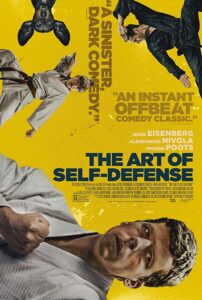

Quirky narrative examines fragile masculinity with violence and dark humor.

The measure of a man, according to the mysterious Sensei, is the ability to punch forcefully with one’s foot. When the meek and unassuming Casey (Jesse Eisenberg) is mugged and left terribly injured, he turns to a local dojo to study Karate. Led by a quietly intimidating man, who merely refers to himself as Sensei (Alessandro Nivola), the school teaches, or should I say preaches, sharpening hand-to-hand combat skills in order to disable or even kill an opponent. The prospect of causing the death of another is handled with a sincere matter-of-fact directness; Sensei is serious about his Karate.

Casey, who works as a bookish accountant at a large, nondescript corporation, decides to take as much time as possible to recuperate from his attack. And as months pass, his rehabilitation progresses under the watchful eye of Sensei and his skeptical second-in-command Anna (Imogen Poots). But as Casey’s teaching advances, he begins to notice disturbing aspects of the school’s curriculum. And when Sensei invites him to the shadowy night class, Casey’s education takes on a more sinister meaning.

“The Art of Self-Defense” is arguably a better film than the much lauded “Fight Club.” While it’s certainly not as hugely entertaining or epic in its sweep, this tiny, intimate film touches artfully on the same themes that distinguished “Fight Club,” and, possibly, with more impact. I suspect that writer/director Riley Stearns had on his offbeat mind David Fincher’s 1999 dazzling ode to eggshell virility when penning the script. And like “Fight Club,” “The Art of Self-Defense” uses dark humor to expose the ever-present insanity that is bubbling underneath the calm, ordinary mainstream male. One could imagine Casey thinking antipathetically about his boss’ cornflower blue tie.

Eisenberg has made a career out of playing characters like Casey. It would be easy to say that the reason the gifted actor often finds himself taking on introverted and nerdy roles is his diminished physical prowess. But Eisenberg does more than just look the part, he seems to understand the sensitive, damaged men he inhabits with an all-knowing ease. And we always embrace his incarnation without even a second thought—it’s the Eisenberg type.

Nivola, an actor who should be more known to audiences, is quietly menacing in an unnerving way. As Sensei, he’s not physically much larger than Eisenberg, but shares Casey’s outsider, fringe status—a neutered and stepped-on, limping male ego. And Nivola uses an emotionally flat tone that is both intimidating and, in a subversively logical way, comforting to the men under his command. He projects sincere and absolute confidence in everything he says. And while he dryly explains that Anna may be an excellent fighter, he follows that up by stating that she will never be better than a man, reasoning that it is just a matter of gender. It’s a twisted philosophy, but one shared widely by the narrow-minded and insecure. This film may be set in a loopy early 1990s alternate universe of sorts, but the truths explored concerning gender prejudice are universal.

Director Stearns last gave us “Faults” in 2014. That film shared the same off-kilter tone as “Art,” mixing in dark humor to comment about mind control and insensitivity in society. And “Faults” was very good, but in “Art,” Stearns digs deeper and delivers a more complete film, one that should propel his career forward. Hopefully, he will stay true to his eclectic origins, especially now that he’s partnered with David and Nathan Zellner (see “Damsel”), who executive produce here.

While “The Art of Self-Defense” is not for everyone, fans of “Fight Club” will be enthused, and folks looking for something odd but still coherent will be beguiled.