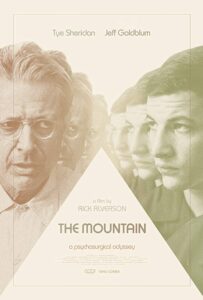

Bizarre and haunting, this lobotomy drama will leave you hollow.

Rick Alverson is a talented director with a unique vision. And with “The Mountain” he proves that he has an idiosyncratic eye and strong voice. He just needs a script that conveys, dare I say, a brighter message.

When the young, introverted Andy (Tye Sheridan) loses his father (Udo Kier), he’s visited by Dr. Wallace Fiennes (Jeff Goldblum). “I knew your father,” the lanky, bespeckled doctor tells Andy. The boy looks up at the man with barely an expression. Over dinner, Fiennes suggests that Andy join him on the road as an assistant. Andy’s job will be to carry the doctor’s gear and to take photographs.

It’s the early 1950s, a time when it was acceptable to treat mental illness with a controversial and crippling procedure known generally as the lobotomy. The process involves poking a barbaric instrument above the eyes and into the brain. The result is a deadening of the patient, and if they patient isn’t paralyzed or killed, the brain is so damaged, the person that once was is not longer there. It was banned, ironically, first in Russia on moral grounds and later in the US in the 1950s, although examples of its use persisted for years.

The fictitious Dr. Fiennes is an expert in this horrifying treatment, methodically inflicting brain damage on those he “treats.” “The Mountain” approaches his work with a cold and calculating frankness. Fiennes is depicted as a devotee to the craft, but who masks his guilt with alcohol and a woman in every port. And Andy has another reason to dislike Fiennes. He knew Andy’s mother.

Bleak and uncompromising, Alverson, working from a script he wrote with Dustin Guy Defa (“Person to Person”) and Colm O’Leary (“The Comedy”), “The Mountain” is an disagreeable and troublesome film. It’s also beautifully shot and acted.

Shot by Lorenzo Hagerman, who lensed Alverson’s 2015 “Entertainment,” the movie is presented in the 1:37:1 aspect ratio. This ratio, which is also referred to as Academy, has become the retro soup du jour these days with Jennifer Kent making use of it in her startling new film “The Nightingale,” and Robert Eggers employing a more extreme narrowing of the image with his upcoming horror film “The Lighthouse.” I’m mixed on the use of this aspect for a drama like “The Mountain,” especially when the images are so vividly captured and dreamily colored. Other than maybe a period reference, what is the narrative purpose of limiting the visual scope? I wonder…

While the narrative subject matter is utterly distasteful, “The Mountain” does offer several terrific performances. Goldblum once again reminds us that he’s one of the most underrated and poorly used actors working today. As Fiennes, he’s a tragic monster, who, at one point, is turned away from an institution only to stare off blankly as though he’s one of his ill-fated patients. There’s a vacant quality to Goldblum’s work here that hints at the actor’s charming charisma, while dimming it into something to be pitied.

Tye Sheridan, the fresh-faced youthful actor who has amassed an impressive filmography at age 22, pulls back here playing Andy as a caged animal. It’s almost too reserved in that Goldblum, who is also required to be dulled, isn’t playing his role big either. But given the material, both performances are just what the doctor ordered. Add on top of that a gonzo turn from French actor Denis Lavant (“Holy Motors”) that dominates the film’s last third, and you have a varied mix. Lavant is certainly an actor who goes for it, and here he adds something very different to the story, but it almost feels out of place. I suppose that his over-acting and exaggerated emotions are meant to be a release for the audience who are grappling with the barbarism associated with the practice of lobotomy, but I found it a bit indulgent and even distracting.

Painfully morbid and unpleasant, “The Mountain” is a necessary film, in that it exposes a dark medical past, but that doesn’t make the movie easy to digest or, God forbid, to enjoy.