“Brooklyn” director gives us the Cliff’s Notes version of a Pulitzer Prize winning novel.

All you need to know about “The Goldfinch” movie is that the “kiss” gets a laugh. Teased in the trailers, we see Boris (played by “it boy” Finn Wolfhard), plant a kiss on Theo’s lips. The audience I saw the film with chuckled. When I came to this epiphany in the book, I teared up. And thinking about it just now, I’m still deeply moved.

Perspective and tone are askew in director John Crowley’s shallow adaptation of Donna Tartt’s bestseller. And it’s a tired excuse to call the source material, that runs almost 800 pages, “unfilmable.” The fact is that Tartt’s book is a very detailed, linear, and vivid coming-of-age journey told exclusively from the perspective of Theodore. The book works largely because we experience his growth from around age 13 through young adult years. We only know what he remembers, and we only see people and things as he sees them.

If you avoid this movie and read the book, you might find yourself talking to your kids a little differently. You might try to listen more and lecture less. For me, the book has had that effect, and maybe it’s not too late to parent better.

By contrast, Crowley, who works from a screenplay by Peter Straughan (see the wonderful “Frank” and the not-so-wonderful “The Snowman”), softens the edge and blurs the perspective. Lost is the nuance that gave the novel its power.

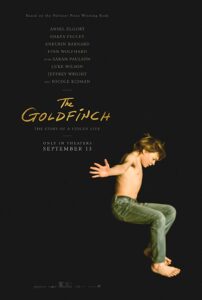

Theodore Decker (played young by Oakes Fegley and older by Ansel Elgort) is an only child living in New York City, with his mother, a his former model and NYU art major. One day, while visiting a museum, the two are caught in the blast of a domestic terror attack. In the chaos, Theo is given a prized ring by a dying man, and he stuffs a famous painting (The Goldfinch, his mother’s favorite) into a shopping bag. He then leaves and walks home, which we learn in the book was the disaster plan he and his mother had previously agreed to in the event something happened. Mom never comes home, and we learn she died in the bombing.

Having no close relatives, his father is no where to be found, Theo goes to live with the Barbour’s, a rich family on Park Avenue. Since the Barbour patriarch is mentally infirm, the affairs are largely managed by Mrs. Barbour (Nicole Kidman), a cold, formal woman with four children. While Theo’s stay with the Barbours is civil, it is lacking in the love and intimacy that the little boy desperately needs. However, when, after a couple months, Theo’s deadbeat father (Luke Wilson) shows up and takes him to Las Vegas, things get much, much worse for the little boy.

Once in Vegas, Theo meets Boris (Wolfhard), a Russian, who lives with his abusive father. In the movie, both boys bond around the death of their mothers, whereas in the book, that fact isn’t the main reason they become friends. In time, Theo will return to NYC and reunite with the kind Hobie (Jeffrey Wright), the partner of the dying man who gave Theo the ring. With him always, Theo carries the painting, constantly worried that he will be caught as a thief, but unable to let it go, because it reminds him of his mother. And Theo additionally harbors guilt that if not for him, his mother may still be alive.

but the screenplay gets the character wrong.

Clocking in at two and a half hours, “The Goldfinch” movie hits the highlights of the novel, merely skimming the surface and failing to develop characters meaningfully. Part of what made the novel work for me is the journey, the disorienting challenges the boy faces from place to place. The movie rushes through them all, instead of narrowly focusing on a few of the key moments and letting them breathe.

For example, Theo’s harrowing Greyhound bus trip (when he was fifteen years old) from Vegas back to NYC takes some 60 hours in the book. Not only does it seem to happen quicker in the movie, but Theo does not appear to be the right age to travel alone. Key note here, in the novel, Theo spends a couple years in Vegas, and he’s only able to travel by Greyhound because he’s fifteen.

Once in NYC, Theo braves the cold streets intending to go to the Barbours but ends up on Hobie’s townhouse doorstep to be magically greeted by his one true love Pippa. For some reason, this is changed in the movie, sapping it somewhat of the magic of that moment, shown in the book through Theo’s memories. It’s possible that Theo’s memories are not entirely accurate, I kept asking myself while reading the book. Lots of incredible coincidences happen, and adults are hard and unfeeling, largely oblivious to Theo’s inner longings and troubles. But in the movie, we are left to take everything literally. The lyrical quality of Tartt’s lovely and remarkably rich prose are utterly lost.

The mechanical, workmanlike structure of Straughan’s screenplay makes use of a flashback device starting with Theo in an Amsterdam hotel room preparing for suicide. There’s a sporadic voice over narration from Theo that is inconsistently used. Through flashback, the idea had to be that earlier elements of the story could be introduced, perhaps, as “glimpses.” The main film narrative would focus on the older Theo, and rely on hot young actor Ansel Elgort (see “Baby Driver”). Sadly, this short shrifts the best parts of the novel, and unfortunately, Oakes Fegley appears to be cast primarily for his facial resemblance to Elgort, because he does not make much impression here. The height difference between the two was distracting for me. Sure, it’s possible he could have shot up overnight, but later this is problematic when he’s reunited with Boris.

Part of the problem with this movie version of “The Goldfinch” might be the money and level of talent involved. Clearly, producers wanted something that could play as wide as possible. And heck, it’s shot by Roger Deakins, making use of the Arri Alexa digital cameras. The result looks fine, but Deakins, hot off his long overdue Oscar win for “Blade Runner 2049?” The rather flat, conservative, even drab images here are not good examples of Deakins’ talents. And unlike the book, where Boris and Theo trip on acid and their visual psychedelic experiences are evocative, detailed, and striking, we get chuckle inducing lines of exposition. Again, perspective is sacrificed.

Capturing a novel on film is fraught with problems. Fans of the printed word will always grumble. But embodying the tone and flavor of the source inspiration is the critical component. Director Crowley and writer Straughan miss this with their adaptation. And while casting and other things can be forgiven, failing to understand why “The Goldfinch” hit readers so personally is unforgivable.

That kiss is really important. It’s so much more than physical, and it might not be physical at all. Laughing was never intended.