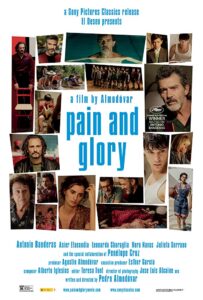

Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar mines elements of his own life in sensitive drama starring Antonio Banderas.

Is it possible that the growth of the pain management industry has turned so many tortured artists into underachievers? In addition to taking lives, the opioid epidemic leaves many survivors less than they could have been. While responsible pain management is required, chronic dependence on medications is an undeniable problem. How many minds have been held back? How much glory lost? Within the thinly-veiled, fictitious narrative of “Pain & Glory,” writer/director Pedro Almodóvar takes us on a personal journey.

He introduces us to troubled film director Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas), whose career has stagnated due to a myriad of physical ailments. One of Salvador’s medical issues caused him to undergo a spinal fusion, which further restricted his ability to direct. But when one of his older movies, entitled “Sabor” (translated as “flavor” or “taste”), gets a new release, memories from the past come flooding back.

In a series of vivid flashbacks, we meet Salvador’s mother, Jacinta (Penelope Cruz), as they move from a city to an idealistic rural village. To Jacinta’s dismay, they take up residence in a cave-dwelling. Despite the cold walls of the underground accommodation, they make it a home. Salvador is a smart child who teaches a local laborer and painter to read and write.

As the re-release of his film nears, Salvador visits Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia), “Sabor’s” lead actor. Thirty years before, the two men had a terrible falling out over Alberto’s performance. But when Salvador knocks, Alberto opens the door.

Salvador’s dependence on opioids has reduced him. And given additional physical limitations, he is forced to crush his pills to powder to swallow them. It seems natural that smoking the illegal opioid heroin or “chasing the dragon” is the next logical step.

While my description of “Pain & Glory” might paint a depressing picture, I assure you that Almodóvar doesn’t want to leave the viewer down. But a little pain here is necessary. And to break things up, Almodóvar skillfully relies on visual story-telling. We learn about Salvador’s body through a series of animations that educate us. It’s interesting, and yet, he holds back just enough to weave a medical mystery of sorts.

To say that this is Banderas’ best performance is a bold statement. The matinee idol, Spanish actor, has been giving audiences great work for over three decades. And now, as he nears 60, he’s given a role that becomes him. It’s a performance that requires a bit of age and world-weariness to get right. Physically, Banderas is in a box here. He painfully moves around, keeping his back stiff, while also adopting just the correct pained expression. And while inhabiting Salvador, the pain both physically and emotionally is written all over his face. It’s an impressive turn and one worthy of awards consideration.

While it might be trite to say a writer should “write what you know,” Almodóvar takes what could be cathartic only for himself and shares it with all of us. I think the title’s familiar ring is telling because neither he nor Banderas could have made this film without drawing on a lifetime of ups and downs.

Pain is the inevitable consequence of being human, and, sadly, some of us have more of it than others. But how we deal with pain is what defines us. And in “Pain & Glory,” the hope that Almodóvar hints at is that channeling the pain is a way of beating the dragon.