Emotionally textured indie offers hopeful take on life’s inconsistencies

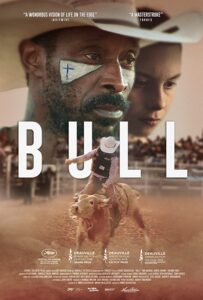

Director Annie Silverstein’s moody character-driven “Bull” would make an essential double feature with Chloé Zhao’s 2017 drama “The Rider.” Both finely cut films focus on the rigors of the rodeo, both physically and emotionally. And in “Bull,” the two lead performances make the emotions connect with the viewer vividly.

When 14-year-old Kris (Amber Havard) finds a hidden key to neighbor Abe’s house, she decides to throw a party. When Abe (Rob Morgan) returns to his home, it’s been trashed. And he catches Kris sleeping on a sofa in the backyard. From there, Abe decides not to press criminal charges in exchange for Kris cleaning up the place.

Their maternal grandmother is raising Kris and her sister. At times, they visit with the children’s mother, who is doing a stint in prison. And as Kris struggles to find her place in the world, there’s a real likelihood that she will follow in her mom’s footsteps.

Reluctantly, Abe takes an interest in keeping Kris busy. After she cleans his place, he takes her with him to the rodeo. Abe was once a star on the bull-riding circuit, but his body and age have relegated him to working in lesser rodeo roles. He helps to distract the bull after it ejects a rider.

But Abe’s no clown. His commitment to the sport extends to training young riders in the craft. And Kris might want to take up the reins.

In her feature debut, Silverstein works from a script that she co-wrote with Johnny McAllister and story consultant Josh Melrod. It’s a gritty indie that takes time to make us appreciate the predicament of the characters. The rough locations drive home the relative poverty of the place, rural Texas, somewhere on the outskirts of Houston. And the creamy, desaturated visuals add to the authenticity of the narrative.

Morgan is excellent as Abe. And his role as an African-American cowboy is fascinating. In some scenes, we see many riders of color traversing the neighborhood on the way to an event. These are striking images that have been mainly ignored in films.

But Silverstein’s script smartly shies away from making race a central issue. Aside from a passing reference, color plays little role in the story. There’s one scene early where Abe catches Kris running from his home; he has her, but then smartly lets her go. He looks around, realizing that there’s a right way to handle this situation. Next, the cops arrive. The rule of law is respected, and economics and color are not an overriding consideration.

The maturity of Silverstein’s production is to be lauded. Like Zhao’s “The Rider,” the success of “Bull” is on the shoulders of the performances. Zhao had Brady Jandreau, a former rodeo star, who played a version of himself, and his family played his family in the film. While that movie was a narrative, it was hard to dismiss that Jandreau had experienced a similar injury and struggled in much the same way as his character struggled.

Inasmuch as “The Rider” was a transcendent example of art imitating life, “Bull” achieves much the same level of genuineness. Part of this is the filmmaking approach that keeps the camera intimate, but Silverstein, whose previous success was 2014’s “Skunk,” gets a big boost by the natural performance of Havard, who makes her screen debut.

“Skunk” was a short film set in much the same environment and featuring young people. “Bull” expands on that reality-based world to give us a warts and all portrayal. Abe is a troubled man, who just might be able to help Kris resist the quick money that crime offers. But Kris might be Abe’s salvation, in that he needs something beyond himself to focus on.

“Bull” does not offer a nice, neat package. Like the inconsistencies of life, nothing is simple; layers must be peeled back to reveal naked truths. “Bull’s” a movie about two very different souls who need each other to become better people. And when the film ends, we know the evolutionary process is in full swing.