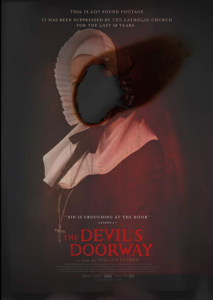

As scary as certain moments in director Aislinn Clarke’s fine horror film “The Devil’s Doorway” are, nothing is scarier than the truth of the Magdalene laundries. They were a real horror show.

Inspired by stories of the institutions that were run on orders from the Catholic Church, “The Devil’s Doorway” is set in a Magdalene laundry, a place in Ireland that housed what were referred to as “fallen women.” The film begins with several paragraphs explaining that the souls imprisoned there were often branded prostitutes and accused of immoral acts.

Inspired by stories of the institutions that were run on orders from the Catholic Church, “The Devil’s Doorway” is set in a Magdalene laundry, a place in Ireland that housed what were referred to as “fallen women.” The film begins with several paragraphs explaining that the souls imprisoned there were often branded prostitutes and accused of immoral acts.

When a statue of the Virgin Mary has been discovered in the laundry weeping blood, Father Thomas Riley (Lalor Roddy) and the younger Father John Thornton (Ciaran Flynn) are dispatched by the Vatican to investigate. Thornton brings along with him filmmaking gear including a 16mm movie camera on which to document everything. And to that end, Thornton and Riley begin production of a documentary of sorts. But what they discover is a disturbing combination of the supernatural and the horribly concrete. The question is whether what is thought to be demonic forces are in reality performing a public service.

When a statue of the Virgin Mary has been discovered in the laundry weeping blood, Father Thomas Riley (Lalor Roddy) and the younger Father John Thornton (Ciaran Flynn) are dispatched by the Vatican to investigate. Thornton brings along with him filmmaking gear including a 16mm movie camera on which to document everything. And to that end, Thornton and Riley begin production of a documentary of sorts. But what they discover is a disturbing combination of the supernatural and the horribly concrete. The question is whether what is thought to be demonic forces are in reality performing a public service.

Calling “The Devil’s Doorway” a found footage film does it a disservice. While the movie is composed of clips assembled after-the-fact (as if later discovered), it is more of a faux documentary in shape. Narrated primarily by Riley, we learn about his religious philosophy and, frankly, why he’d be chosen by the Church to investigate this claim of a miracle. Riley explains that he believes in God, but God isn’t everywhere.

Calling “The Devil’s Doorway” a found footage film does it a disservice. While the movie is composed of clips assembled after-the-fact (as if later discovered), it is more of a faux documentary in shape. Narrated primarily by Riley, we learn about his religious philosophy and, frankly, why he’d be chosen by the Church to investigate this claim of a miracle. Riley explains that he believes in God, but God isn’t everywhere.

Riley encourages the naive Thornton to look for God in the terrible institution. And to that end, the filmmaker-in-training takes his camera and attempts to do just that. He’s shut down, of course, by secretive nuns led by the imposing Mother Superior (Helena Bereen).

Is it a reasonable conclusion that God is in that place? Riley answers the question with a definite “no.” He’s a skeptic, one that’s been around and seen a great many bad things in his life. And as the cynical Riley, actor Roddy conveys a real sense of world-weary experience. It’s a terrific performance and one reminiscent of the late Jason Miller who played the besieged Father Karras in the “The Exorcist.” Make no mistake, filmmaker Clarke well knows that by casting the angular Roddy they are clearly winking at Friedkin’s classic.

Is it a reasonable conclusion that God is in that place? Riley answers the question with a definite “no.” He’s a skeptic, one that’s been around and seen a great many bad things in his life. And as the cynical Riley, actor Roddy conveys a real sense of world-weary experience. It’s a terrific performance and one reminiscent of the late Jason Miller who played the besieged Father Karras in the “The Exorcist.” Make no mistake, filmmaker Clarke well knows that by casting the angular Roddy they are clearly winking at Friedkin’s classic.

There are moments of sheer terror in “The Devil’s Doorway.” But what I found most interesting about the film were the seemingly banal conversations that Riley has with his younger associate. Riley is educating the youth, while at the same time, not trying to restrain his curiosity. And when Riley pontificates plainly about existential questions, you want to know more about him and the things he’s seen in his life. He’s a simple guy on the surface, but he speaks Greek and casts himself headfirst into a dangerous situation.

As the sense of foreboding becomes ever more intense, Riley appears to accept the fate that he’s been dealt. When he confronts Mother Superior, he knows that he’s putting himself at risk. And when Riley attempts to do the right thing for one girl he finds chained in a subterranean dungeon of sorts, he knows that God isn’t going to save him, Thornton, the girl, or any of their souls. It’s really chilling.

As the sense of foreboding becomes ever more intense, Riley appears to accept the fate that he’s been dealt. When he confronts Mother Superior, he knows that he’s putting himself at risk. And when Riley attempts to do the right thing for one girl he finds chained in a subterranean dungeon of sorts, he knows that God isn’t going to save him, Thornton, the girl, or any of their souls. It’s really chilling.

The 16mm visual scope (an approximate 4:3 aspect ratio) is a risky choice by Clarke, whose marvelous short film “Childer” was an exquisitely shot artistic horror entry. By comparison, “The Devil’s Doorway” is ugly, almost low resolution, and dirty. But this is all intentional, and the choice, after a short period of adjustment, makes complete sense, placing you in the place and time wonderfully. You begin to feel the grime of the place, as the camera documents the investigation without giving entirely into the nauseating “Blair Witch” shaky cam.

The other masterful choice is setting the “The Devil’s Doorway” in a Magdalene laundry. I remember, years ago, speaking with Peter Mullan about his excellent film “The Magdalene Sisters.” Mullan had been inspired to write and ultimately make the movie by a chance, late night, viewing of a documentary about the institutions. And he also recounted watching footage of one of the laundries where he believed the priest was directing the girls to act a certain way. I observed then that Mullan’s film seemed like a psychological horror movie. The real horror is the reality of the girls wrongfully called “fallen women.” Sometimes, in the name of God, the other guy takes over.

The other masterful choice is setting the “The Devil’s Doorway” in a Magdalene laundry. I remember, years ago, speaking with Peter Mullan about his excellent film “The Magdalene Sisters.” Mullan had been inspired to write and ultimately make the movie by a chance, late night, viewing of a documentary about the institutions. And he also recounted watching footage of one of the laundries where he believed the priest was directing the girls to act a certain way. I observed then that Mullan’s film seemed like a psychological horror movie. The real horror is the reality of the girls wrongfully called “fallen women.” Sometimes, in the name of God, the other guy takes over.