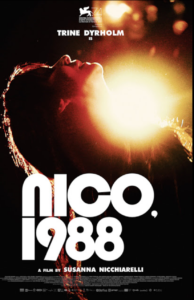

Boosted by a searing, uncanny performance from Trine Dyrholm, “Nico, 1988” is a telling time capsule.

In 1988, singer Christa Päffgen a.k.a Nico (played by Danish actress Dyrholm) embarked on her final tour. The once striking German model and rocker had deteriorated at age 49, but still retained her deep, emotive vocal sound. And the music comes across remarkably in writer/director Susanna Nicchiarelli’s unique mini-biopic. So too does the film convey the troublesome and tortured personality traits that led to Nico’s decline. It’s a rich, textured portrait.

In 1988, singer Christa Päffgen a.k.a Nico (played by Danish actress Dyrholm) embarked on her final tour. The once striking German model and rocker had deteriorated at age 49, but still retained her deep, emotive vocal sound. And the music comes across remarkably in writer/director Susanna Nicchiarelli’s unique mini-biopic. So too does the film convey the troublesome and tortured personality traits that led to Nico’s decline. It’s a rich, textured portrait.

Chronicling events over the last year of Nico’s life, we see her battling a nasty heroin addiction and struggling to make and perform music. The movie gives us a series of small concerts and the travel and conflict in between. By the time we meet her, Nico has had a rocky relationship with her son Ari (Sandor Funtek). The young man has followed his famous mother into the depths of drug addiction. While Nico understands her son, she without the necessary tools to save herself, let alone him.

“Nico, 1988” works best when Dyrholm performs Nico’s music. She has the vocal intonations down perfectly. And although I have nothing to judge this by, her characterization of Nico offstage is very special and seem like they’d be accurate. The attitude, detached and emotionless, then irrational, the wild eyes, it is in keeping with my experiences with people who are stricken with addiction. But there’s also a tenderness to the performance particularly when Nico interacts with her worried son.

Presented in 4:3, an ratio that is now thought of as a retro aspect, cinematographer Crystel Fournier (“Girlhood”), places the camera almost exclusively on Dyrholm, every ugly wrinkle and track mark captured. The camera is calm when necessary, spending time with Nico, as she shoots up, argues with those around her, and records ambient sounds with a portable recorder she carries with her.

And when Nico takes the stage, Fournier’s camera comes alive moving rhythmically with the music. Dyrholm’s mimicry of Nico’s guttural howl booms forth in one concert sequence as the camera moves as if commanded by the performer. It’s bloody good work, cut together with archived concert footage of the real Nico.

However, one question that is left unanswered by Nicchiarelli’s film is what is Nico’s legacy? She was survived by her son, but where does she sit in rock and roll history? This film feels very personal, focusing on the small dramatic issues, but if you’re a fan and want to know about Nico’s larger body of work, this film will leave you wanting.

It is important to note that I typically like biopics that focus closely on one event that shaped the subject. I’m not sure that Nicchiarelli captures a single important event or even a couple of significant ones. Instead, she defines her subject in a very intimate way. We get an idiosyncratic feel for the character of the singer, if not what motivated her.

None of the famous people that made up Nico’s younger years makes an appearance in this narrative. Based on what we learn in this film, it is as if she was abandoned and left to succumb to her addiction. The sadness of Nico’s situation is moving, especially when you hear and see the music performed in such a fine and astonishing way by Dyrholm. “Nico, 1988” is a solid character piece about an enigmatic personality.