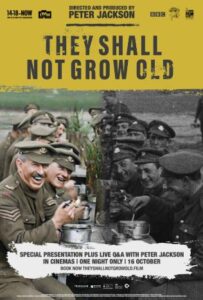

Peter Jackson brings his skills to the documentary form with unusual results and heart wrenching impact.

When I heard about Brazilian artist Marina Amaral’s skillful colorization of Holocaust victim photos, I was instantly curious. Was this a good thing? A registration picture of Czeslawa Kwoka, who was murdered by lethal injection, was perfectly enhanced to vivid color revealing previously unappreciated detail. Posted to Twitter, the photo garnered much attention and a new appreciation for the tragedy.

By using rotoscoping, high tech audio editing, and epic cinematic story-telling skills, Oscar winning director Peter Jackson weaves together the history of World War I British infantry. Like the work of colorization expert Amaral, Jackson’s efforts provide a new perspective on the battlefield experience. It’s a humbling, significant achievement, one that may frustrate some viewers and enchant others. Regardless, the emotional impact is undeniable.

Jackson combed through 600 hours of audio interviews with World War I soldiers in order to seamlessly patch together the harrowing story of British infantry fighting in France. As a preface to the film that screened for critics in Atlanta, the filmmaker sat down intimately before a camera with a cup of coffee in his hand and talked briefly about how he came to this project. He was approached by the Imperial War Museum (IWM) and the BBC about taking their film and audio archives and doing something. In fact, they told him he could do just about anything with their archives. Such artistic freedom is either a blessing or a curse.

So, after some tests, Jackson decided to treat the stills and film material with the highest technology available. Not only does he enhance the footage, but the techniques colorize and add detail as well as retiming the frame rates. It’s quite a job, and the result ranges from breathtaking to off-putting. At times, the images blur, intentionally, and faces take on a somewhat cartoonish quality. The effects are strange and haunting and presented in immersive 3D.

But as much as the techniques may be distracting and questioned, the narrative is something special. Told exclusively through the voices of the infantryman, we hear from those that experienced the horrors of war. And the detail there is stunning. The grand tale starts naturally at the beginning as young men, some as young as 15 years old (who lied about their age), join the cause and are trained by the military. But what became immediately apparent was that the armed forces infrastructure was ill-prepared for the influx of so many new recruits.

In time, the men receive basic skills and are shipped off to battle. We see them learn how to dress, shoot guns, and be taught hand-to-hand combat with the expert use of the bayonet. It is this part of the film that will frustrate viewers as they become acclimated to the visual and story-telling approach. The early scenes have imagery projected over old recruiting posters and literature. I found this visual scope to be too limiting, but this is just the set up for what is to follow—an immersion into the field of battle unlike anything I’ve see before.

And once the fighting starts, we see these young impressional minds go through hell on earth. As horses pull guns from place to place, the technology of the battlefield shifts to early tanks, the secret weapon, that roll over the bombed out countryside. The shear horror of it all is unimaginable. Long portions of the film are devoted to exploring the terrain that becomes scarred and utterly destroyed, devoid of life. It’s painful to watch, giving viewers an armchair appreciation for what it must have been like.

What struck me as the credits roll was the huge number of voices credited. We hear from all walks of life, and they frankly give us a first person account of events that need to be remembered. And regardless of the special effects wizardry involved, their voices tower above it all. And the humanity that is on display is deeply moving, as the German soldiers surrender and the British infantry must deal with prisoners that, like them, would rather be anywhere else. The respect paid to their fellow soldiers is stunning, and it was caught on film.

As I look at the colorized photo of Czeslawa Kwoka, whose face reflects the terror of that time, I’m glad that effort was taken to bring the image from flatter black and white to something approximating our reality. And after seeing “They Shall Not Grow Old” I wish we could have heard Kwoka’s voice, because the power of hearing from those that went through and experienced unspeakable events may in some small way help us all to understand. And through understanding perhaps healing can contribute to preventing such tragedies in the future.