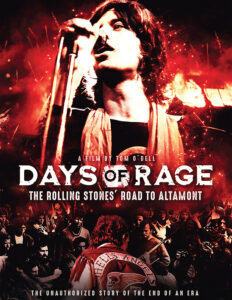

Handsomely made rock doc is companion piece to “Gimme Shelter.”

By relying on an impressive amount of archived material, director Tom O’Dell provides an expository history lesson of the end of the sixties’ dream. The tragic events at Altamont that culminated in the stabbing death of 18-year-old Meredith Hunter by a member of the Hells Angels act as an epic cautionary tale. “Days of Rage” gives us context as to how such a thing could have happened.

Starting with the Beatles invasion and ending with the December 1969 free concert at Altamont Speedway in California, we learn that the Rolling Stones evolved as a kind of foil of the “happy” music that enchanted the world from the Fab Four. O’Dell briskly covers world events both within the rock universe and as to geopolitical factors. The rise of the Stones is placed against the backdrop of the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr. The growing objections to the Vietnam War are examples of the development of 1960’s counterculture.

The concept of the “free” concert had caught on, especially with the hugely popular landmark Woodstock music festival. The Rolling Stones missed Woodstock for several reasons. And the idea of a free concert event was hatched by the Stones and the Grateful Dead. We learn the decision to mount the concert at Altmont was made mostly out of necessity. By contrast, the iconic Maysles picture “Gimme Shelter,” we see famed attorney Melvin Belli negotiating the contract for the event.

While O’Dell’s movie travels a lot of the same ground as 1970’s “Shelter,” it is a much more grounded expository affair. Therefore, we get a series of voices, some like tour producer Robbie Schneider and tour manager Sam Cutler, providing first-hand accounts. These stories blend with more scholarly commentaries from writers, like Joel Selvin, author of “Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day.”

First-person accounts are plentiful, although none of the principal musicians are interviewed. Therefore, we hear from journalist Michael Lydon, who was on the scene and first reported on the tragedy, but we do not hear from Mick Jagger directly. Still, the music is prominently featured, including previously unseen footage from the festival.

“Days of Rage” convincingly presents the position that a confluence of factors resulted in what has been called “Rock’s Darkest Day.” But ultimately, the Hells Angels receive the brunt of the blame. An effort is made to differentiate between some gang members, brought into the counterculture by Timothy Leary, and the violent Hells Angels that provided de facto “security” for the event.

But repeated images of motorcycle gang members viciously wielding pool cues as a means of crowd control are hard to watch. And the footage of the stabbing itself, which is said to exist, does not appear in the film.

on December 6, 1969 in Livermore, California.

(Photo by Robert Altman/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Once the movie moves from historical context to the Altamont concert itself, O’Dell does build significant tension leading to the terrifying and bloody death. What we don’t get is coverage of the criminal prosecution for Hunter’s death, which is repeatedly referred to as “murder” throughout the closing moments of the film. A trial resulted in an acquittal of Hells Angel Alan Passaro. The jury, who is said to have viewed the footage, concluded that the stabbing was in self-defense.

“Days of Rage” is ultimately about the end of the flower power era. It’s essential viewing for anyone interested in this period in history. And it’s a documentary that makes an excellent companion piece to the Maysles’ “Gimme Shelter” or D.A. Pennebaker’s “Monterey Pop.”