By delivering storytelling without pretense, writer/director Alfonso Cuarón reminds us of the power of pure dramatic cinema.

“Roma” gives us the mundanities of life. Our protagonist, Cleo (Yaltza Aparicio), works as a nanny for a middle class family in the Colonia Roma district of Mexico City. It’s the early 1970s, a time of political strife. Her employers, Sofia and Antonio, aren’t people of great wealth, but they are financially secure. Their residence provides room to accommodate four children and Sofia’s mother. Cleo lives in a detached apartment. Along with fellow worker Adela (Nancy Garcia Garcia), we see Cleo performing various domestic duties, primarily taking care of the children. And it is clear that the little ones love and adore her, with the youngest boy sharing a bond that is normally reserved for that of a mother and her child.

“Roma” gives us the mundanities of life. Our protagonist, Cleo (Yaltza Aparicio), works as a nanny for a middle class family in the Colonia Roma district of Mexico City. It’s the early 1970s, a time of political strife. Her employers, Sofia and Antonio, aren’t people of great wealth, but they are financially secure. Their residence provides room to accommodate four children and Sofia’s mother. Cleo lives in a detached apartment. Along with fellow worker Adela (Nancy Garcia Garcia), we see Cleo performing various domestic duties, primarily taking care of the children. And it is clear that the little ones love and adore her, with the youngest boy sharing a bond that is normally reserved for that of a mother and her child.

In one early, subtle scene that warms the heart, Cleo and the little boy share a moment on a rooftop. Lying on her back with her head opposite the child’s, she comforts him from a position of carefully judged understanding. It’s a perfect display of empathy rarely found in movies these days. Cleo relates to the youngster and everyone around her in a special way—from a place of unbridled innocence. By saying very little, she tells us so much. “Roma” is a film about stolen moments, conveyed without manipulation.

Taking place over a period of months, we see Cleo outside the household. Her boyfriend, Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero), studies martial arts. In one scene, Cleo visits him in the desert where he is training with a large group. They are visited by an expert, who leads the class in a lesson in which he closes his eyes and strikes a pose. As the students struggle to get into position, some of them falling over and unable to copy the teacher, Cleo effortlessly performs the exercise. No attention by others is paid to Cleo’s feat, but we see it, and we know what this means.

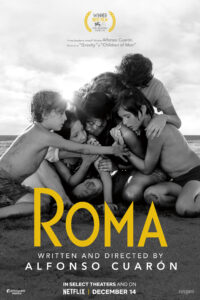

Cuarón’s first feature since winning the Oscar for 2013’s “Gravity,” “Roma” seems far removed from that science fiction tale. However, what ties the two movies together is his commitment to character and familial hardships. But missing from this production is Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, with whom Cuarón worked not only on “Gravity” but on 2006’s “Children of Men” and Cuarón’s breakthrough 2001’s “Y Tu Mamá También.”

Surprisingly, Cuarón steps in and lenses “Roma” himself. By employing the Arri Alexa 65, he digitally recorded the film in 6.5K employing the 2.35.1 aspect ratio. This makes a small story appear large and sumptuous, giving this tiny fable epic visual treatment. Cuarón also made the bold choice to present the movie in black and white. It’s a collection of classic and striking images that will likely garner him nominations for cinematography. Talk is that he may find himself nominated in many categories, including directing, writing, and for his camera work. All of this praise is well-deserved.

A personal story for Cuarón, it is easy to believe that “Roma” is a somewhat autobiographic, drawing on real experiences from his childhood in Mexico. There is a level of detail here that resonates universally. For example, Cuarón gives us an opening title sequence shot against the stones of the family’s driveway entrance. Cleo is washing this spot, removing the detritus left by their dog. This becomes a recurring reference throughout the movie. Cuarón is determined to revisit real images, giving us the mundane things that compose one’s memory of things past. And some of these memories are unpleasant and immensely sad, but they are worth remembering, because they matter.

Few films this year impacted me more than “Roma.” Movies like Chloé Zhao’s “The Rider” or Bing Liu’s “Minding the Gap” brought us inside intimate experiences that shape personalities. And while we can be spirited away with wonderfully colorful and exciting fantasies like the much lauded “Black Panther,” there is room in our cinematic lives for real stories about real people that are painful to watch, but leave us better off because we did not close our eyes.